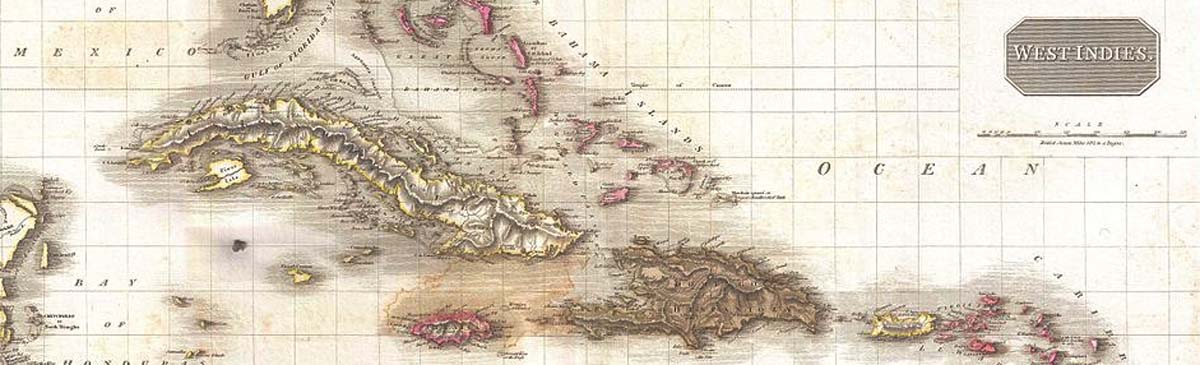

Caribbean

Caribbean Ports: ° Anguilla ° Antigua and Barbuda ° Antilles ° Aruba ° Bahamas ° Barbados ° Cuba ° Dominica ° Dominican Republic (Santo Domingo) ° Grenadines ° Guadeloupe ° Haiti ° Jamaica ° Martinique ° Netherlands/Antilles ° Puerto Rico ° Saint Kitts ° St. Lucia ° St. Martin ° St. Thomas ° St. Vincent and the Grenadines ° Tortola ° Trinidad and Tobago ° Turks and Caicos

Dominican Republic

For at least 5,000 years before Christopher Columbus sailed into the Americas from Europe, the island, which he named Hispaniola, had been inhabited by Amer-Indians for thousands of years from a blending of waves of immigrants and were called "Taino," a word meaning "good" or "noble" in their language.

When Columbus landed on the island he named Hispaniola he wrote in his journal of the beauty of the island, including high, forested mountains and large river valleys. He described the Ta no as very peaceful, generous and cooperative with the Europeans, and as a result, the Europeans saw the Ta no as easy targets with gold ornaments and jewelry from the deposits found in Hispaniola's rivers. So after a month or so of feasting and exploring the northern coast of Hispaniola, Columbus returned to Spain to announce his discovery; because he lost his flagship, he left sailors behind.

The first permanent European settlement, Isabella, was named in 1493, on the north coast of the island. From there the Spaniards could exploit the gold in the Cibao Valley in the interior of the country. The Spaniards brought horses and dogs, and combined with their armor and iron weapons, as well as disease germs against which the Taino had no immunities, the Taino were unable to resist for long.

Unlike Europeans, Africans, and Asians (who had exchanged diseases for centuries along with commercial goods), the Taino, like the native people of North America, had no immunities to the diseases that the Spaniards and their animals carried to the Americas. Forced into brute labor and unable to take time to engage in agricultural activities in order to feed themselves, famine accelerated the death rate.

By the middle of the 17th century, the island of Tortuga, located to the west of Cap Haitien, had been settled by smugglers, run-away indentured servants, and members of crews of various European ships.

The French, envious of Spain's possessions in the Americas, sent colonists to settle Tortuga and the northwestern coast of Hispaniola, which the Spaniards had totally abandoned by 1603. In order to domesticate the pirates, the French supplied them with women who had been imprisoned when accused of prostitution and thieving. The western third of Hispaniola became a French possession called Saint Dominique in 1697, and over the next century developed into what became one of the richest colonies in the world.

|

Sir J. T. Duckworth's action off St. Domingo February 6, 1806 Thomas Whitcombe. |

In 1822, fearful the French would mount another expedition from Spanish Santo Domingo to re-establish slavery, as they had threatened to do, Haiti's president Jean-Pierre Boyer sent an army that invaded and took over the eastern portion of Hispaniola. Haiti once again abolished slavery and incorporated Santo Domingo into the Republic of Haiti.

For the next 22 years the island of Hispaniola was under Haitian control. Due to their loss of political and economic control, the the former Spanish ruling class deeply resented the occupation; during the late 1830's, an underground resistance group, La Trinitaria, was organized under the leadership of Juan Pablo Duarte. After multiple attacks on the Haitian army, and because of internal discord among the Haitians, the Haitians eventually retreated. Independence of the eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola was officially declared on February 27, 1844, and the name Rep blica Dominicana (Dominican Republic) was adopted.

During the 19th century, the country's economy shifted from ranching to other sources of revenue. In the southwestern region, a new industry arose with the cutting down and exporting of precious woods like mahogany, oak and guayac n. In the northern plains and valleys around Santiago, industry focused on growing tobacco for some of the world's best cigars, and on coffee.

March 7, 1865, Sacramento Daily Union, Sacramento, California, USA

The Abandonment of San Domingo by Spain

(From a Madrid letter, January 7th.)

The following is the text of tho bill presented to the Cortes by Marshal Narvaez, abolishing the Decree of the 19th , of May, 1861, declaring the territory of the Dominican Republic "reincorporated into the Spanish Monarchy:

To the Cortes: In the old Spanish island, the first land of the Western world which the great Christopher Columbus considered worthy of an important establishment; in that great Antilles where, many years after its separation from the metropolis, not a drop of Spanish blood was shed, now flows that generous blood, and the rigors of a pestiferous climate aiding the enemy make terrible ravages in the ranks of our valiant soldiers.

This sanguinary struggle, which is also attended by the disadvantage of uselessly and profitlessly expending the public treasure and consuming the abundant products of our colonial possessions, was not provoked by the attempts of anterior Cabinets to carry out an ambitious war of conquest, so opposed to the rational, just, pacific and disinterested policy so long observed by Spain. Neither did it originate from the necessity of repelling foreign aggressions, of opposing force to force at any cost, considering only the defense of insulted honor; such was not the case. This cruel struggle commenced the day following that on which her Majesty's Government of that day believed that all the inhabitants of the Dominican Republic asked and solicited with impatient desire to lie reincorporated with the Spanish nation, their ancient mother, and to form one of its provinces, aspiring to the happiness enjoyed by Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Such a desire might not be certain, but it was very probable. The Government, actuated by these sentiments, had faith in, that which appeared to inspire the Dominicans, and, therefore, accepted their votes, and counseled her Majesty to effect the annexation which this State professed so ardently to desire.

On this account the ministers, in a solemn document, described this event as auspicious, highly honorable for Spain, and one not often encountered in the annals of peoples. For this, also, after referring to the lamentable history of San Domingo, since the proclamation of its independence, in 1821, following the example of other provinces of the American continent alter drawing the sad picture of such prolonged misfortune, of a state of things in which the sources of public and private wealth were exhausted, independence completely lost for want of strength to maintain it, liberty no less, lost through the insecurity felt by the citizens and the continual agitation of the republic the ministers invoked every sentiment of justice, humanity and honor in counseling the annexation _of this unhappy island. They believed such a measure was all the more desirable, considering the circumstances and character of its inhabitants, the" fertility of its soil, and the strong attachment which the people, after past excesses, whereby they had been terribly disabused, professed towards their ancient metropolis.

The annexation was thus founded upon two most noble, just and weighty reasons. The first was the right inherent in the unanimous will of a people, a right not disputed, and previously anirmed by the general assent of the nations of Europe and America in a recent case. The second was the duty of humanity, of compassion toward the unfortunate people who sought favor and mercy, overwhelmed as they were by a sea of disasters and misfortune. No other right supported nor supports the Spanish Government in holding the Spanish portion of the island of San Domingo ; neither the right of revindication nor the right of conquest, both being opposed to the policy of the Government, the interests of the people, and the friendly relations which Spain has always endeavored to maintain with the independent States of America, which once formed part of the immense territory protected by the tutelary mantle of king of Spain.

But such flattering hopes soon disappeared; fatal symptoms very soon manifested themselves that the annexation had not the spontaneous and unanimous support upon which it was based. Nevertheless, it was the duty of the Government to ascertain with certainty whether those violent protests, several times repeated, did not proceed only from a discontented few, but were the expression or the feeling of the people who rejected the legitimate power they had invoked in a time of trouble and distress. The agitation increased and gained towns and frontiers, extending over the whole of the territory, and at this day the Spanish portion of the island of San Domingo presents to the civilized world the spectacle of an entire people in arms ungratefully resisting a tyrants those whom they called in as preservers.

So strange a political phenomenon has been examined by the Ministers undersigned with delicate attention and deep study. They have thoroughly sifted the sad history of the annexation of San Domingo, and have considered the question from every point of view imaginable, commencing by those of justice and right, and last regarding those of expediency. They have well taken into account the reasons that might be alleged on the ground of the national honor and respect, and have considered the event of the most brilliant future possible a triumph obtained at the cost of immense sacrifices; they have weighed the arguments for and against that may be based upon considerations of national and foreign policy; and finally, have carefully made the sad calculation of the numerous and precious lives that Spain loses every day that this sterile contest is prolonged, and of the great amount of treasure it consumes. As a result of this laborious examination the Ministers are impressed with the conviction that the question of San Domingo has reached a point wnich will allow us to make the following deductions:

That" it was a delusion to believe that the Dominican people, as a whole, or in the great majority, desired, and, above all, demanded their annexation to Spain. That the struggle having become general, it does not now bear the character of a measure taken to subject a few discontented rebels, but of a war of conquest completely foreign to the spirit of Spanish policy. That even by concentrating our efforts and sacrifices in order to obtain a triumph we should place ourselves in the sad position of holding the island entirely by military occupation, full of difficulties and not exempt from dangerous complications. That even under the most favorable hypothesis, that a portion of the population may show themselves devoted to us after victory, the governmental system that would have to be established in those dominions must either be little suitable to the usages and customs of the inhabitants, or very, dissimilar to that of the other colonial provinces.

Upon all these and other considerations which the superior intelligence of the Cortes will supp'y, the Ministers, anxious to put an end to the useless sacrifices in men and money which the war in San Domingo imposes upon the nation, have the honor to propose being duly authorized by her Majesty the following project of law:

ART I. The royal decree of the 19th of May, 1861, declaring the Territory of the Dominican republic reincorporated with the monarchy is repealed.

ART. 2. The Government is authorized to take the neces.ai y measures for the execution of this law, giving account of the same to the Cortes.

DUKE OF VALENCIA, President of the Council.

ANTONIO BENAVIDES, Minister for Foreign Affairs.

LORENZO ARRAZOLA, Minister of Grace and Justice.

BARZANALLANA, Minister of Finance.

CORODVA, Minister of War.

ARMERO, Minister of Marine.

LUIS GONZALES BRAVO, Minister of the Interior.

GALIANO, Minister of Public Works.

SEIJAS LOZANO, Minister of the Colonies.

April 26, 1869, The New York Herald, New York, New York, USA

St. Domingo

Progress of the Annexation Idea Counter Influences at Work

Napoleon's Plan for a West Indian Confederation

St. Domingo, April 2, 1869

|

The Dominican Republic: |

The idea of annexation to or some form of protection from the United States is taking possession of the Dominican mind to an incredible extent. In a recent trip In a recent trip into the interior sections, where the African population largely preponderates and where we least expected such an exhibition of interest, we were overwhelmed with inquiries as to when the Americans were coming. Almost everybody has something he expects to sell to the Americans for their "beautiful gold and silver." Lands, cattle horses, pigs, poultry even are to find a cash market when the "Americans shall take charge of Dominican prosperity."

There is a secret but steady counter current at work, however, which will take a distinct form should Congress refuse to authorize the President to effect the annexation. One and all deny the soft impeachment, but it is not the less true, nevertheless that at least two or the European consuls have united in urging a counter plan upon the Dominican Cabinet, and that one member (but one, I believe) decidedly prefers the European plan to the policy of annexation to the United States. Some members of the Senate say that while the vote for annexation would undoubtedly be unanimous, if proffered by the United States, the counter plan is equally sure to work out the independent prosperity of the island. It is even asserted, but not on official authority that I can learn, that the inspiration comes from the Tuileries, because a gentleman from Paris has been the chief advocate among the Dominican merchants of non-annexation.

The counter plan looks to the confederation of Cuba, Haiti, Porto Rico and Jamaica, possibly, under a European recognition which shall amount to an efficient protection of the Republic of the Antilles, it is thought here that such a pressure could be brought upon Spain by France, England and other powers, that Spain would give up Cuba to the Cubans for a few million francs upon the condition that Cuba shall remain an Independent State and agree to grant something like permanent free trade for Spanish ships.

If the Dominican republic will renounce the idea or annexation to the United States and declare the ports of Samana and Monte Christo free and neutral ports, valuable aid and countenance will be rendered the Baez government through a bank which parties stand ready to establish, taking the mining rents as a security for the loan now in abeyance.

The mere discussion of annexation has done much for the relief of Baez, coming up as it did contemporaneously with the Cuban revolution. It became evident to the alert consular agents of Europe that the Grant administration would have the power to add these three islands Cuba, Haiti and Porto Rico to the Union, whether Europe was pleased or not; no nation on the other side of the water would venture beyond a little quiet intrigue to prevent it; but should the United States be disinclined to annex just now, what then? Why, endeavor to make future annexation possible. Can this be done? Here it is believed by many that it is not only feasible, but in some degree pre-arranged to defeat the annexation of the Antilles by means of St. Domingo. If the ocean cable should suddenly flash the intelligence that Napoleon had forestalled the Grand Cabinet in recognizing that Cuba "a whole people struggling for their existence as a distinct nationality," and in asking Spain to grant them the political boon of independence, both Spain and the Cubans will be apt to heed the advice of this strong mediator. In advance of this, the Dominican republic will have learned exactly what it has to expect from the United States. If the flat should be free acceptance into the Union Cuba will not hear of any other destiny for herself than annexation. Neither will France waste much diplomacy to rescue Cuba from Spain if the island of Haiti second only to Cuba in importance is given over to the United States. But with both islands amenable to European influence, with all their products and tariffs arranged to meet the interests of European manufactures and commerce, the affair is worth managing.

In 1882, General Ulysses Heureux came into power. His brutal dictatorship consisted of a corrupt regime that maintained power by violent repression of his opponents. Following his assassination in 1899, several individuals came to power, only to be rapidly overthrown by their political opponents, and the country's internal situation continuously degenerated into chaos.

Around the turn of the century, the sugar industry was revived, and so many Americans came to the Dominican Republic to buy plantations that they came to dominate this vital sector of the economy. In 1916, Americans, wanting to expand their influence and power used the First World War as an excuse to bring in U.S. Marines to "protect it" against vulnerability to large European powers such as Germany. They had used this argument just prior to send in U.S. Marines to occupy Haiti.

December 30, 1882, Pacific Rural Press, California

Stand to Your Guns.

Smugglers. Ivan Constantinovich Aivazovsky.

Stand to your guns! Close the ranks front and rear,

With jour face to the foe, no repining, no fear;

Raise high our proud banners, now lowered at hall mast,

Where it ruefully hangs, all the mourners have passed.

Stand to your guns! Save the ship, clear the wreck,

The tars of Columbia must muster on deck;

Launch again on the ocean the flag of the free,

The pirates and smugglers to sweep from the sea.

Then cast overboard every sailor who skulks

From his duty or colors, who grumbles, or sulks

With a mutinous snarl or sneer on his lip,

While pirates are plundering and scuttling the ship.

Drum out every soldier who sneaks from the ranks

While the foe Is assailing the front and the flanks;

Comrades who desert while the battle is hot,

By the laws of all nations are doomed to be shot.

Drive out the camp rubbish, who bluster and brag,

The cravens who stand not by gun or by flag;

The Hessians, who battle for rations and pay,

Are sure to surrender, desert, or betray.

In contests for freedom, for country, or creed,

Deserters and trimmers can never succeed;

The soldier in siege, or in field, who has won—

Is he who has loyally stood by his gun.

The past has its glories, the present its hour

To break every fetter that curbs freedom's power,

New duties arise and new triumphs must come

Full freedom for women and froedom from rum.

Then close up the ranks—let the battle begin

There are fields to be fought, there are sieges to win;

There are legions to conquer- warm work to be done—

Then muster each man who wi'l stand to his gun.

C. J. Beattie

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.