Sandwich Islands

Mark Twain in Hawaii

° Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) ° The Hawaiian Archipelago (Isabella Bird) ° Captain Cook in Hawaii ° Joaquin Miller ° Missionaries ° Mark Twain

New York Tribune, January 6, 1873, New York, New York

By Mark Twain

Sir: When you do me the honor to suggest that I write an article about the Sandwich Islands, just now when the death of the King has turned something of the public attention in that direction, you un-kennel a man whose modesty would have kept him in hiding otherwise. I could fill you full of statistics, but most human beings like gossip better and so you will not blame me if I proceed after the largest audience and leave other people to worry the minority with arithmetic.

I spent several months in the Sandwich Islands, six years ago, and if I could have my way about it, I would go back there and remain the rest of my days. It is paradise for an indolent man. If a man is rich he can live expensively, and his grandeur will be respected as in other parts of the earth; if he is poor he can herd with the natives, and live on next to nothing; he can sun himself all day long under the palm trees, and be no more troubled by his conscience than a butterfly would.

When you are in that blessed retreat, you are safe from the turmoil of life; you drowse your days away in a long deep dream of peace; the past is a forgotten thing, the present is heaven, the future you leave to take care of itself. You are in the center of the Pacific Ocean; you are two thousand miles from any continent; you are millions of miles from the world; as far as you can see, on any hand, the crested billows wall the horizon, and beyond this barrier the wide universe is but a foreign land to you, and barren of interest.

The climate is simply delicious -- never cold at the sea level, and never really too warm, for you are at the half-way house -- that is, twenty degrees above the equator. But then you may order your own climate for this reason: the eight inhabited islands are merely mountains that lift themselves out of the sea -- a group of bells, if you please, with some (but not very much) "flare" at their bases. You get the idea.

Well, you take a thermometer, and mark on it where you want the mercury to stand permanently forever (with not more than 12 degrees variation) Winter and Summer. If 82 in the shade is your figure (with the privilege of going down or up 5 or 6 degrees at long intervals), you build your house down on the "flare" -- the sloping or level ground by the sea-shore -- and you have the deadest surest thing in the world on that temperature. And such is the climate of Honolulu, the capital of the kingdom. If you mark 70 as your mean temperature, you build your house on any mountain side, 400 or 500 feet above sea level. If you mark 55 or 60, go 1,500 feet higher. If you mark for Wintry weather, go on climbing and watching your mercury.

If you want snow and ice forever and ever, and zero and below, build on the summit of Mauna Kea, 16,000 feat up in the air. If you must have hot weather, you should build at Lahaina, where they do not hang the thermometer on a nail because the solder might melt and the instrument get broken, or you should build in the crater of Kilauea, which would be the same as going home before your time. You can not find as much climate bunched together anywhere in the world as you can in the Sandwich Islands.

Sunrise Over Diamond Head. Jules Tavernier. 1888

You may stand on the summit of Mauna Kea, in the midst of snow-banks that were there before Capt. Cook was born, maybe, and while you shiver in your furs you may cast your eye down the sweep of the mountain side and tell exactly where the frigid zone ends and vegetable life begins; a stunted and tormented growth of trees shades down into a taller and freer species, and that in turn, into the full foliage and varied tints of the temperate zone; further down, the mere ordinary green tone of a forest washes over the edges of a broad bar of orange trees that embraces the mountain like a belt, and is so deep and dark a green that distance makes it black; and still further down, your eye rests upon the levels of the seashore, where the sugar-cane is scorching in the sun, and the feathery cocoa-palm glassing itself in the tropical waves, and where you know the sinful natives are toiling about in utter nakedness and never knowing or caring that you and your snow and your chattering teeth are so close by. So you perceive, you can look down upon all the climates of the earth, and note the kinds of colors of all the vegetation, just with a glance of the eye -- and this glance only travels over about three miles as the bird flies, too.

The natives of the islands number only about 50,000, and the whites about 3,000, chiefly Americans. According to Capt. Cook the natives numbered 400,000 less than a hundred years ago. But the traders brought labor and fancy diseases -- in other words, long, deliberate, infallible destruction; and the missionaries brought the means of grace and got them ready. So the two forces are working along harmoniously, and anybody who knows anything about figures can tell you exactly when the last Kanaka will be in Abraham's bosom and his islands in the hands of the whites. It is the same as calculating an eclipse -- if you get started right, you cannot miss it. For nearly a century the natives have been keeping up a ratio of about three births to five deaths, and you can see what that must result in. No doubt in fifty years a Kanaka will be a curiosity in his own land, and as an investment will be superior to a circus.

I am truly sorry that these people are dying out, for they are about the most interesting savages there are. Their language is soft and musical, it has not a hissing sound in it, and all their words end with a vowel. They would call Jim Fisk Jimmy Fikki, for they will even do violence to a proper name if it grates too harshly in its natural state. The Italian is raspy and disagreeable compared to the Hawaiian tongue.

These people used to go naked, but the missionaries broke that up; in towns the men wear clothing now, and in the country a plug hat and a breech-clout; or if they have company they put on a shirt collar and a vest. Nothing but religion and education could have wrought these admirable changes. The women wear a single loose calico gown, that falls without a break from neck to heels.

In the old times, to speak plainly, There was absolutely no bar to the commerce of the sexes. To refuse the solicitations of a stranger was regarded as a contemptible thing for a girl or a woman to do; but the missionaries have so bitterly fought this thing that they have succeeded at least in driving it out of sight -- and now it exists only in reality, not in name.

These natives are the simplest, the kindest-hearted, the most unselfish creatures that bear the image of the Maker. Where white influence has not changed them, they will make any chance stranger welcome, and divide their all with him -- a trait which has never existed among any other people, perhaps. They live only for today; tomorrow is a thing which does not enter into their calculations. I had a native youth in my employ in Honolulu, a graduate of a missionary college, and he divided his time between translating the Greek Testament and taking care of a piece of property of mine which I considered a horse. Whenever this boy could collect his wages, he would go and lay out the entire amount, all the way up from fifty cents to a dollar, in poi (which is a paste made of the taro root, and is the national dish), and call in all the native ragamuffins that came along to help him eat it. And there, in the rich grass, under the tamarind trees, the gentle savages would sit and gorge till all was gone. My boy would go hungry and content for a day or two, and then some Kanaka he probably had never seen before would invite him to a similar feast, and give him a fresh start.

Hawaiian Fish, Oapukai |

The ancient religion was only a jumble of curious superstitions. The shark seems to have been the god they chiefly worshiped -- or rather sought to propitiate. Then there was Pele, a goddess who presided over the terrible fires of Kilauea; minor gods were not scarce. The natives are all Christians, now -- every one of them; they all belong to the church, and are fonder of theology than they are of pie; they will sweat out a sermon as long as the Declaration of Independence; the duller it is the more it infatuates them; they would sit there and stew and stew in a trance of enjoyment till they floated away in their own grease if the ministers would stand watch -- and -- watch, and see them through. Sunday-schools are a favorite dissipation with them, and they never get enough. If there was physical as well as mental intoxication in this limb of the service, they would never draw a sober breath. Religion is drink and meat to the native. He can read his neatly printed Bible (in the native tongue -- every solitary man, woman, and little child in the islands can), and he reads it over and over again. And he reads a whole world of moral tales, built on the good old Sunday-school book pattern, exaggerated, and he worships their heroes -- heroes who wale the world with their mouths full of butter, and who are simply impossibly chuckle-headed and pious. And he knows all the hymns you ever heard in your life, and he sings them in a soft, pleasant voice, to native words that make "On Jordan's stormy banks I stand" sound as grotesquely and sweetly foreign to you as if it were a dictionary grinding wrong end first through a sugar-mill. Now you see how these natives, great and small, old and young, are saturated with religion -- at least the poetry and the music of it. But as to the practice of it, they vary. Some of the nobler precepts of Christianity they have always practiced naturally, and they always will. Some of the minor precepts they as naturally do not practice, and as naturally they never will. The white man has taught them to lie, and they take to it pleasantly and without sin -- for there cannot be much sin in a thing which they cannot be made to comprehend is a sin. Adultery they look upon as poetically wrong but practically proper.

These people are sentimentally religious -- perhaps that describes it. They pray and sing and moralize in fair weather, but when they get into trouble, that is "business" -- and then they are tolerably apt to drop poetry and call on the Great Shark God of their fathers to give them a lift. Their ancient superstitions are in their blood and bones, and they keep cropping out now and then in the most natural and pardonable way.

I am one who regards missionary work as slow and discouraging labor, and not immediately satisfactory in its results. But I am very far from considering such work either hopeless or useless. I believe that such seed, sown in savage ground, will produce wholesome fruit in the third generation, and certainly that result is worth striving for. But I do not think much can reasonably be expected of the first and second generations. It is against nature. It takes long and patient cultivation to turn the bitter almond into the peach. But we do not refrain from the effort on that account, for, after all, it pays.

The natives make excellent seamen, and the whalers would rather have them than any other race. They are so tractable, docile and willing, and withal so faithful, that they rank first in sugar-planters' esteem as laborers. Do not these facts speak well for our poor, brown Sunday-school children of the far islands!

There is a small property tax, and any native who has an income of $50 a year can vote.

The 3,000 whites in the islands handle all the money and carry on all the commerce and agriculture -- and superintend the religion. Americans are largely in the majority. These whites are sugar-planters, merchants, whale-ship officers, and missionaries. The missionaries are sorry that most of the other whites are there, and these latter are sorry the missionaries don't migrate. The most of the belt of sloping land that borders the sea and rises toward the bases of the mountains, is rich and fertile. There are only 200,000 acres of this productive soil, but only think of its capabilities! In Louisiana, 200,000 acres of sugar land would only yield 50,000 tons of sugar per annum, and possibly not so much; but in the Sandwich Islands, you could get at least 400,000 tons out of it. This is a good, strong statement, but it is true, nevertheless. Two and a half tons to the acre is a common yield in the islands; three and a half tons is by no means unusual; five tons is frequent; and I can name the man who took fifty tons of sugar from seven acres of ground, one season. This cane was on the mountainside, 2,500 feet above sea level, and it took it three years to mature. Address your inquiries to Capt. McKee, Island of Mani, S.I. Few plantations are stuck up in the air like that, and so twelve months is ample time for the maturing of cane down there. And I would like to call attention to two or three exceedingly noteworthy facts. For instance, there you do not hurry up and cut your cane when it blossoms, but you just let it alone and cut it when you choose -- no harm will come of it. And you do not have to keep an army of hands to plant in the planting season, grind in the grinding season, and rush in frantically and cut down the crop when a frost threatens. Not at all. There is no hurry. You run a large plantation with but a few hands, because you plant pretty much when you please, and you cut your cane and grind it when it suits your convenience. There is no frost, and the longer the cane stands the better it grows. Sometimes -- often, in fact -- part of your gang are planting a field, another part are cutting the crop from an adjoining field, and the rest are grinding at the mill. You only plant once in three years, and you take off two ratoon crops without replanting. You may keep on taking off ratoon crops about as long as you please, indeed; every year the bulk of the cane will be smaller, but the juice will grow regularly denser and richer, and so you are all right. I know of one lazy man who took off sixteen ratoon crops without replanting!

What fortunes those planters made during our war, when sugar went up into the twenties! It had cost them about ten or eleven cents a pound, delivered in San Francisco, and all charges paid. Now if any one desires to know why these planters would probably like to be under our flag, the answer is simple: We make them pay us a duty of four cents a pound on refined sugars at present; brokerage, freights and handling (two or three times), costs three cents more; rearing the cane, and making the sugar, is an item of five cents more -- total, 12 cents a pound, or within a cent of it, anyhow. And today refined sugar is only worth about 12 cents (wholesale) in our markets. Profit -- none worth mentioning. But if we were to annex the islands and do away with that crushing duty of four cents a pound, some of those heavy planters who can hardly keep their heads above water now, would clear $75,000 a year and upward. Two such years would pay for their plantations, and all their stock and machinery. It is so long since I was in the islands that I feel doubtful about swearing that the United States duty on their sugars was four cents a pound, but I can swear it was not under three.

I would like to say a word about the late King Kamehameha V. and the system of government, but I will wait a day. Also, I would like to know why your correspondents so calmly ignore the true heir to the Sandwich Islands throne, as if he had no existence and no chances; and I would like to heave in a word for him. I refer to our stanch American sympathizer, Prince William Lunalilo, descendant of eleven generations of sceptered savages -- a splendid fellow, with talent, genius, education, gentlemanly manners, generous instincts, and an intellect that shines as radiantly through floods of whisky as if that fluid but fed a calcium light in his head. All people in the islands know that William -- or "Prince Bill," as they call him, more in affection than otherwise -- stands next to the throne; and so why is he ignored?

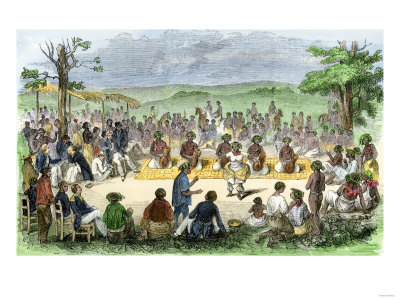

Native Dance Performance for Sailors in the Sandwich Islands. 1850s |

The Sandwich Islands: Concluding Views of Mark Twain

New York Tribune , January 9, 1873 New York, New York

By Mark Twain

Sir: Having explained who the 3,000 whites are, and what sort of people the 50,000 natives are, I will now shovel in some information as to how this toy realm, with its toy population, is governed. By a constable and six policemen? By a justice of the peace and a jury? By a mayor and a board of aldermen? Oh, no. But by a King -- and a Parliament -- and a Ministry -- and a Privy Council -- and a standing army (200 soldiers) -- and a navy (steam ferry-boat and a raft) -- and a grand bench of supreme justices -- and a lord high sheriff on each island. That is the way it is done. It is like propelling a sardine dish with the Great Eastern's machinery.

Something over 50 years ago the natives, by a sudden impulse which they could not understand themselves, burned all their idols and overthrew the ancient religion of the land. Curiously enough, our first invoice of missionaries were sailing around the Horn at the time, and they arrived just in season to furnish the people a new and much better means of grace. They baptized men, women, and children at once and by wholesale, and proceeded to instruct them in the tenets of the new religion immediately afterward. They built enormous churches, and received into communion as many as 5,000 people in a single day. The fame of it went abroad in the earth, and everywhere the nations rejoiced; the unworldly called it a "great awakening," and even the unregenerated were touched, and spoke of it with admiration.

The missionaries learned the language, translated the Bible and other books into it, established schools, and even very complete colleges, and taught the whole nation to read and write; the princes and nobles acquired collegiate educations, and became familiar with half a dozen dead and living languages. Then, some twenty years later, the missionaries framed a constitution which became the law of the land. It lifted woman up to a level with her lord; placed the tenant less at the mercy of his landlord; it established a just and equable system of taxation; it introduced the ballot and universal suffrage; it defined and secured to king, chiefs, and people their several rights and privileges; and it instituted a parliament in which all the estates of the realm were to be represented, and, if I remember rightly, it gave this parliament power to pass laws over the King's veto.

Things went on swimmingly for several years, and especially under the reign of the late King's brother, an enlightened and liberal-minded prince; but when he died and Kamehameha V. ascended the throne, matters took a different turn. He was one of your swell "grace of God" Kings, and not the "figure-head" some have said he was; indeed, he was the biggest power in the Islands all his days, and his royal will was sufficient to create a law any time or overturn one.

He was master in the beginning, and at the middle, and to the end. The Parliament was the "figure-head," and it never was much else in his time. One of his very first acts was to fly into a splendid passion (when his Parliament voted down some measure of his), and tear the beautiful Constitution into shreds, and stamp on them with his royal No. 18s! And his next act was to violently prorogue the Parliament and send the members about their business. He hated Parliaments, as being a rasping and useless encumbrance upon a king, but he allowed them to exist because as an obstruction they were more ornamental than real. He hated universal suffrage and he destroyed it -- at least, he took the insides out of it and left the harmless figure. He said he would not have beggars voting industrious people's money away, and so he compelled the adoption of a cash qualification to vote. He surrounded himself with an obsequious royal Cabinet of American and other foreigners, and he dictated his measures to them and, through them, to his Parliament; and the latter institution opposed them respectfully, not to say apologetically, and passed them.

This is but a sad kind of royal "figure-head." He was not a fool. He was a wise sovereign; he had seen something of the world; he was educated and accomplished, and he tried hard to do well by his people, and succeeded. There was no trivial royal nonsense about him; he dressed plainly, poked about Honolulu, night or day, on his old horse, unattended; he was popular, greatly respected, and even beloved. Perhaps the only man who never feared him was "Prince Bill," whom I have mentioned heretofore. Perhaps the only man who ever ventured to speak his whole mind about the King, in Parliament and on the hustings, was the present true heir to the throne -- if Prince Bill is still alive, and I have not heard that he is dead. This go-ahead young fellow used to handle His Majesty without gloves, and wholly indifferent to consequences; and being a shade more popular with the native masses than the King himself, perhaps, his opposition amounted to something. The foregoing was the common talk of Honolulu six years ago, and I set the statements down here because I believe them to be true, and not because I know them to be true.

Prince William is about 35 years of age, now, I should think. There is no blood relationship between him and the house of the Kamehameha's. He comes of an older and prouder race; a race of imperious chiefs and princes of the Island of Maui, who held undisputed sway there during several hundred years. He is the eleventh prince in direct descent, and the natives always paid a peculiar homage to his venerable nobility, which they never vouchsafed to the mushroom Kamehameha's. He is considered the true heir to the Hawaiian throne, for this reason, viz.: A dying or retiring king can name his own successor, by the law of the land -- he can name any child of his he pleases, or he can name his brother or any other member of the royal family. The late king has passed away without leaving son, daughter, brother, uncle, nephew, or father (his father never was king -- he died a year or two ago), and without appointing a successor. The Parliament has power now to elect a king, and this king can be chosen from any one of the twelve chief families. This has been my understanding of the matter, and I am very sure I am right. In rank, Prince William overtops any chief in the Islands about as an English royal duke overtops a mere earl. He is the only Hawaiian, outside of the royal family, who is entitled to bear and transmit the title of Prince; and he is so popular that if the scepter were put to a popular vote he would "walk over the track."

He used to be a very handsome fellow, with a truly princely deportment, drunk or sober; but I merely speak figuratively -- he never was drunk; he did not hold enough. All his features were fine, and he had a Roman nose that was a model of beauty and grandeur. He was brim full of spirit, pluck and enterprise; his head was full of brains, and his speech was facile and all alive with point and vigor; there was nothing underhanded or two-faced about him, but he always went straight at everything he undertook without caring who saw his hand or understood his game. He was a potent friend of America and Americans. Such is the true heir to the vacant throne -- if he is not dead, as I said before.

I have suggested that William drinks. That is not an objection to a Sandwich Islander. Whisky cannot hurt them; it can seldom even tangle the legs or befog the brains of a practiced native. It is only water with a flavor to it, to Prince Bill; it is what cider is to us. Poi is the all-powerful agent that protects the lover of whisky. Whoever eats it habitually may imbibe habitually without serious harm. The late king and his late sister Victoria both drank unlimited whisky, and so would the rest of the natives if they could get it. The native beverage, awa, is so terrific that mere whisky is foolishness to it. It turns a man's skin to white fish-scales that are so tough a dog might bite him, and he would not know it till he read about it in the papers. It is made of a root of some kind. The "quality" drink this to some extent, but the Excise law has placed it almost beyond the reach of the plebeians. After awa, what is whisky?

Many years ago the late King and his brother visited California, and some Sacramento folks thought it would be fun to get them drunk. So they gathered together the most responsible soakers in the town and began to fill up royalty and themselves with strong brandy punches. At the end of two or three hours the citizens were all lying torpid under the table and the two princes were sitting disconsolate and saying what a lonely, dry country it was! I tell it to you as it was told to me in Sacramento.

The Hawaiian Parliament consists of half a dozen chiefs, a few whites, and perhaps thirty or forty common Kanakas. The Kings ministers (half a dozen whites) sit with them and ride over all opposition to the King's wishes. There are always two people speaking at once -- the member and the public translator. The little legislature is as proud of itself as any parliament could be, and puts on no end of airs. The wisdom of a Kanaka legislature is as profound as that of our ordinary run of State legislatures, but no more so. Perhaps God makes all legislatures alike in that respect. I remember one Kanaka bill that struck me: it proposed to connect the islands of Oahu and Hawaii with a suspension bridge, because the sea voyage between these points was attended with so much sea-sickness that the natives were greatly discommoded by it. This suspension bridge would have been 150 miles long!

I can imagine what is going on in Honolulu now, during this month of mourning, for I was there when the late King's sister, Victoria, died. David Kalakaua (a chief), Commander-in-Chief of the Household Troops (how is that, for a title?) is no doubt standing guard now over the closed entrances to the "palace" grounds, keeping out all whites but officers of State; and within, the Christianized heathen are howling and dancing and wailing and carrying on in the same old savage fashion that obtained before Cook discovered the country. I lived three blocks from the wooden two-story palace when Victoria was being lamented, and for thirty nights in succession the morning pow-wow defied sleep. All that time the Christianized but morally unclean Princess lay in state in the palace. I got into the grounds one night and saw some hundreds of half-naked savages of both sexes beating their dismal tom-toms, and wailing and caterwauling in the weird glare of innumerable torches; and while a great band of women swayed and jiggered their pliant bodies through the intricate movements of a lascivious dance called the hula-hula, they chanted an accompaniment in native words. I asked the son of a missionary what the words meant. He said they celebrated certain admired gifts and physical excellencies of the dead princess. I inquired further, but he said the words were too foul for translation; that the bodily excellencies were unmentionable; that the capabilities so lauded and so glorified had better be left to the imagination.

He said the King was doubtless sitting where he could hear these ghastly praises and enjoy them. That is, the late King -- the educated, cultivated Kamehameha V. And mind you, one of his titles was "the Head of the Church;" for, although he was brought up in the religion of the missionaries, and educated in their schools and colleges, he early learned to despise their plebeian form of worship, and had imported the English system and an English bishop, and bossed the works himself. You can imagine the Saturnalia that is making the night hideous in the palace grounds now, where His Majesty is lying in state.

Kamehameha V, Hawaiian King (1830-1872)

The late King was frequently on hand in the royal pew in the Royal Hawaiian Reformed Catholic Church, on Sundays, but whenever he got into trouble he did not fly to the cross for help -- he flew to the heathen gods of his ancestors. Now this was a man who would write you a beautiful letter, in a faultless hand, and word it in faultless English; and perhaps throw in a few graceful classic allusions; and perhaps a few happy references to science, international law, or the world's political history; or he would array himself in elegant evening dress and entertain you at his board in princely style, and converse like a born Christian gentleman; and day after day he would work like a beaver in affairs of State, and on occasion exchange autograph letters with the kings and emperors of the old world. And the very next week, business being over, he would retire to a cluster of dismal little straw-thatched native huts by the sea-shore, and there for a fortnight he would turn himself into a heathen whom you could not tell from his savage grandfather. He would reduce his dress to a breech-clout, fill himself daily full of whisky, and sit with certain of his concubines while others danced the peculiar hula-hula. And if oppressed by great responsibilities he would summon one of his familiars, an ancient witch, and ask her to tell him the opinion and the commands of the heathen gods, and these commands he would obey. He was so superstitious that he would not step over a line drawn across a road, but would walk around it. These matters were common talk in the Islands. I never saw this King but once, and then he was not on his periodical debauch. He was in evening dress attending the funeral of his sister, and had a yard of crepe descending from his stovepipe hat.

If you will be so good as to remember that the population of the islands is but a little over 50,000 souls, and that over that little handful of people roosts a monarchy with its coat-tails fringed with as many mighty-titled dignitaries as would suffice to run the Russian Empire, you will wonder how, the offices all being filled, there can be anybody left to govern. And the truth is, that it is one of the oddest things in the world to stumble on a man there who has no title. I felt so lonesome, as being about the only unofficial person in Honolulu, that I had to leave the country to find company.

After all this exhibition of imperial grandeur, it is humiliating to have to say that the entire exports of the kingdom are not as much as $1,500,000, the imports in the neighborhood of that figure, and the revenues, say $500,000. And yet they pay the King $36,000 a year, and the other officials from $3,000 to $8,000 -- and heaven knows there are enough of them.

The National Debt was $150,000 when I was there -- and there was nothing in the country they were so proud of. They wouldn't have taken any money for it. With what an air His Excellency the Minister of Finance lugged in his Annual Budget and read off the impressive items and flourished the stately total!

The "Royal Ministers" are natural curiosities. They are white men of various nationalities, who have wandered thither in times gone by. I will give you a specimen -- but not the most favorable. Harris, for instance. Harris is an American -- a long-legged, vain, light-weight village lawyer from New Hampshire. If he had brains in proportion to his legs, he would make Solomon seem a failure; if his modesty equaled his ignorance, he would make a violet seem stuck-up; if his learning equaled his vanity, he would make von Humboldt seem as unlettered as the backside of a tombstone; if his stature were proportioned to his conscience, he would be a gem for the microscope; if his ideas were as large as his words, it would take a man three months to walk around one of them; if an audience were to contract to listen as long as he would talk, that audience would die of old age; and if he were to talk until he said something, he would still be on his hind legs when the last trump sounded. And he would have cheek enough to wait till the disturbance was over, and go on again.

Such is (or was) His Excellency Mr. Harris, his late Majesty's Minister of This, That, and The Other -- for he was a little of everything; and particularly and always he was the King's most obedient humble servant and loving worshiper, and his chief champion and mouthpiece in the parliamentary branch of ministers. And when a question came up (it didn't make any difference what it was), how he would rise up and saw the air with his bony flails, and storm and cavort and hurl sounding emptiness which he thought was eloquence, and discharge bile which he fancied was satire, and issue dreary rubbish which he took for humor, and accompany it with contortions of his undertaker countenance which he believed to be comic expression!

Robert Louis Stevenson with King Kalakaua and Lloyd Osbor

He began in the islands as a little, obscure lawyer, and rose to be such a many-sided official grandee that sarcastic folk dubbed him, "the wheels of the Government." He became a great man in a pigmy land -- he was of the caliber that other countries construct constables and coroners of. I do not wish to seem prejudiced against Harris, and I hope that nothing I have said will convey such an impression. I must be an honest historian, and to do this in the present case I have to reveal the fact that this stately figure, which looks so like a Washington monument in the distance, is nothing but a thirty-dollar windmill when you get close to him.

Harris loves to proclaim that he is no longer an American, and is proud of it; that he is a Hawaiian through and through, and is proud of that, too; and that he is a willing subject and servant of his lord and master, the King, and is proud and grateful that it is so.

Now, let us annex the islands. Think how we could build up that whaling trade! Though under our courts and judges it might soon be as impossible for whale-ships to rendezvous there without being fleeced and "pulled" by sailors and pettifoggers as it now is in San Francisco -- a place the skippers shun as they would rocks and shoals. Let us annex. We could make sugar enough there to supply all America, perhaps, and the prices would be very easy with the duties removed. And then we would have such a fine half-way house for our Pacific-plying ships; and such a convenient supply depot and such a commanding sentry-box for an armed squadron; and we could raise cotton and coffee there and make it pay pretty well, with the duties off and capital easier to get at. And then we would own the mightiest volcano on earth -- Kilauea! Barnum could run it -- he understands fires now. Let us annex, by all means. We could pacify Prince Bill and other nobles easily enough -- put them on a reservation. Nothing pleases a savage like a reservation -- a reservation where he has his annual hoes, and Bibles and blankets to trade for powder and whisky -- a sweet Arcadian retreat fenced in with soldiers.

By annexing, we would get all those 50,000 natives cheap as dirt, with their morals and other diseases thrown in. No expense for education -- they are already educated; no need to convert them -- they are already converted; no expense to clothe them -- for obvious reasons.

We must annex those people. We can afflict them with our wise and beneficent government. We can introduce the novelty of thieves, all the way up from street-car pickpockets to municipal robbers and Government defaulters, and show them how amusing it is to arrest them and try them and then turn them loose -- some for cash and some for "political influence." We can make them ashamed of their simple and primitive justice. We can do away with their occasional hangings for murder, and let them have Judge Pratt to teach them how to save imperiled Avery-assassins to society. We can give them some Barnards to keep their money corporations out of difficulties. We can give them juries composed entirely of the most simple and charming leatherheads. We can give them railway corporations who will buy their Legislatures like old clothes, and run over their best citizens and complain of the corpses for smearing their unpleasant juices on the track. In place of harmless and vaporing Harris, we can give them Tweed. We can let them have Connolly; we can loan them Sweeny; we can furnish them some Jay Goulds who will do away with their old-time notion that stealing is not respectable. We can confer Woodbull and Claflin on them. And George Francis Train. We can give them lecturers! I will go myself.

We can make that little bunch of sleepy islands the hottest corner on earth, and array it in the moral splendor of our high and holy civilization. Annexation is what the poor islanders need. "Shall we to men benighted, the lamp of life deny?"

San Francisco Call, October 4, 1894, San Francisco, California

SMUGGLING OPIUM

Grave Charges Against Steamboat Men.

A Big Price Paid for the Drug at Honolulu-

A Remnant of the Emerald Gang at Work.

When the trial of the Emerald smugglers closed a few months ago the local representatives of the Government, the District Attorney, the Special Agent of the Treasury and the Collector of the port rejoiced and were exceedingly glad, for they believed that they had broken up one of the strongest rings that ever existed on this coast.

But the heavy burden of punishment laid upon the unhappy trio now in San Quentin did not daunt their confederates in crime. While the prisoners were before the bar battling for liberty, their associates were at work in this city, in Victoria and in Honolulu buying, smuggling and selling the drug.

Vessels as fleet as the Emerald were passing through the Golden Gate at night bearing a forbidden cargo to be sold in Chinatown or shipped to the Hawaiian Islands.

The Collector of the Port was not long in ignorance of the fact that the remnant of the ring was working as hard as ever. The manufacture and exportation of opium at Victoria did not cease. The revenue officers still found the drug in Chinatown and news came from Honolulu that it was being sold there to the victims of the pipe and syringes.

The Hawaiian laws absolutely prohibit the importation and sale of opium, yet it is a well known fact it can be procured with little difficulty by all who want it. The opium cooked in California and known here as domestic opium costs in this city about $4 a pound. It sells in the Hawaiian republic at $18 a pound.

The opium made in Victoria is sold in Honolulu for $24 a pound and the Simon pure article from, Hong Kong sells for $28 a pound. Therefore it pays to smuggle opium into the islands, always provided that the smuggler is not caught.

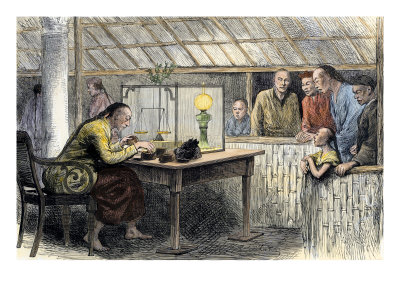

Chinese Merchant Weighing Opium, 1880s |

The drug that is taken from Victoria to Honolulu first comes to this city and here placed on a vessel bound to Honolulu, where it falls into the hands of the ring, who find away to sell it to the natives.

Collector Wise believes, and has in his possession facts that warrant his belief, that the opium is taken from this city to the Islands on one of the steamers, and believes that trusted employes of the steamship company are members of of or are in the employ of the ring.

The Collector, convinced that the employes of the company are smuggling, but being unable to procure the proper kind of evidence against them, wrote to the agent of the company on Monday stating the facts in his possession, and urging the removal of suspects. He stated last night that he had received no reply to the letter, and that he did not care to discuss the matter.

1899. World's Fleet. Boston Daily Globe

Lloyds Register of Shipping gives the entire fleet of the world as 28,180 steamers and sailing vessels, with a total tonnage of 27,673,628, of which 39 perent are British.

| Great Britain | 10,990 vessels, total tonnage of 10,792,714 |

| United States | 3,010 vessels, total tonnage of 2,405,887 |

| Norway | 2,528 vessels, tonnage of 1,604,230 |

| Germany | 1,676 vessels, with a tonnage of 2,453,334, in which are included her particularly large ships. |

| Sweden | 1,408 vessels with a tonnage of 643, 527 |

| Italy | 1,150 vessels |

| France | 1,182 vessels |

For Historical Comparison

Top 10 Maritime Nations Ranked by Value (2017)

| Country | # of Vessels | Gross Tonnage (m) |

Total Value (USDbn) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greece | 4,453 | 206.47 | $88.0 |

| 2 | Japan | 4,317 | 150.26 | $79.8 |

| 3 | China | 4,938 | 159.71 | $71.7 |

| 4 | USA | 2,399 | 55.92 | $46.5 |

| 5 | Singapore | 2,662 | 64.03 | $41.7 |

| 6 | Norway | 1,668 | 39.68 | $41.1 |

| 7 | Germany | 2,923 | 81.17 | $30.3 |

| 8 | UK | 883 | 28.78 | $24.3 |

| 9 | Denmark | 1,040 | 36.17 | $23.4 |

| 10 | South Korea | 1,484 | 49.88 | $20.1 |

| Total | 26,767 | 87.21 | $466.9 | |

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.