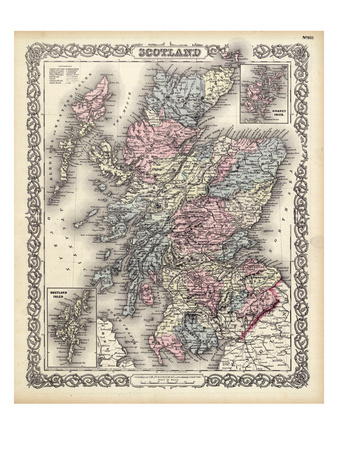

Scotland

° Aberdeen ° Dundee ° Edinburgh ° Glasgow ° Hebrides ° Inverness ° Shetland and Orkney Islands ° St. Andrews ° Unicorns

The Hebrides

In the ancient stones of these islands there is much prehistory . . . The duns and brochs, the menhirs and stone circles, the chambered cairns.

1855, Scotland and Islands |

The Standing Stones of Callernish were old when Rome was yet unborn, as W. C. MacKenzie puts it in one of the works from which we have already quoted. Ancient structures, such as the broch known as Dun Carloway, were in use centuries, if not millenia, before our northern kingdom became known as Scotland.

Standing Stones of Callanish, Callanish |

The subterranean dwellings and stone huts of the Isles must have been very old, indeed, by the time the Scots crossed over from Ireland to Dalriada, in Argyll. From the eighth century onwards, the Norsemen of Viking times continued to come over the seas and settle in these parts.

Dunvegan Castle, Isle of Skye, Inner Hebrides

They came not just as plunderers, ready to depart whenever they had despoiled the countryside: on the contrary, they arrived with the intention of remaining. And they certainly remained some centuries. But for the defeat and destruction of King Haco’s fleet at Largs in 1263, there is no saying how long thereafter the Norse domination of the Western Isles might have continued.

In 1788, a sheep-stealer was placarded and led through the streets of Stornoway by the common executioner, to receive, upon his bare back, and at each of five appointed places, no fewer than ten lashes. Banishment, either for life or for a long period of years, usually followed public whippings for such offences as sheep-stealing which, in olden times, was considered as heinous an offence as anyone could commit.

A woman convicted of theft in 1820 was sentenced to be led from prison by a rope tied round her neck, and to carry on her breast a placard proclaiming her, in large letters, to be a habitual and reputed thief. Thereafter she was put in the pillory for a couple of hours. Her sentence included seven years’ banishment.

Loch Leathan, the Old Man of Storr. Isle of Skye, Inner Hebrides |

June 10, 1843, Colonial Gazette, London, United Kingdom

SHOVELLING OUT PAUPERS.

MANY have smiled at the quaint appositeness of the phrase in which Mr. BULLER described the prevalent mode of encouraging emigration; but too few have thought of its terribly literal truth. The papers relating to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, in the last Parliamentary Blue Book on "Colonial Lands and Emigration," contain illustrations in plenty of the process of "shovelling out paupers."

"With few exceptions," wrote Mr. DODD, from Cape Breton, in November 1841, "all the emigrants arriving this season at Sydney came from the western islands of Scotland, possessing means the most limited, and with few resources among themselves beyond the ability to undergo privations peculiar to the settlement of a new country. The little property they possessed in Scotland was sold to realise a sufficient sum to defray the expenses of their passage to Cape Breton, and the emigrant agents, as they are called, were heartless enough to impose upon these poor people, by making them pay before their embarkation, the head-money formerly levied by an act of the Legislature of this province, but which was repealed last winter; and thus leaving them, on their arrival here, so perfectly destitute of means as to throw them on the bounty of others for the expense of transporting their families and luggage to the residence of their friends in the interior of the country, who will be obliged to support them until next year."

Mr. CRAWLEY wrote from the same, place about a month earlier: "There has not been any inquiry for land made at this office from more than two or three out of 1500 emigrants from the Hebrides, arrived during this year; and they confessed that their intentions were not to purchase, but to ascertain where vacant land was to be found, in order that they might immediately settle upon it, without purchase or permission. I understand that the greater number of them repaired, soon after their debarkation, to the tract of land known as the old Mira grant, which is the common resort and resource of those Scotch emigrants who are not in circumstances to acquire land by purchase; and where, as the proprietors are absent and the Government does not interfere, the strongest helps himself, and the weak takes What is left him." Government cannot prevent this squatting, for, as Lord FALKLAND remarks in a despatch of December 1841,

"The settler who wishes to establish himself without paying for the ground he occupies, can do so unembarrassed by any fear of opposition on the part of the Government; enormous grants of wild land having been made to absentees, who have no representatives in Nova Scotia, he has only to fix his habitation on one of these tracts, and reside in security, undisturbed either by the Crown or by the legal owner of the soil."

The poor emigrants from Scotland are driven to squat from the impossibility of finding employment. "I am of opinion," writes the Collector of Customs at Halifax, "that the labourers who arrive here from St. John's and New Brunswick are sufficient for any demand for labour in the colony."

Here is a picture of the process of "shovelling out paupers," and its consequences. During the war, the prices of kelp rose high, and the landowners in the Hebrides encouraged the growth of a large kelp-making population. Since the peace, barilla has come to supply the place of kelp, and the kelp-makers have become paupers. All the landowners are more or less embarrassed large estates are managed by trustees in behalf of the creditors it was difficult to find food for the paupers, and they were "shovelled out" to Nova Scotia. No less than 1500 were shovelled out in 1841; in the three years of which that was the last, 3000 were shovelled out. In 1842, about 1677 were shovelled out. No questions were asked as to how the paupers were to support themselves when they reached their destination: they were sent with money and provisions barely sufficient to enable them to reach their journey's end, to a country where their labour might or (for anything those who sent them knew) might not avail to procure them subsistence. The owners of property connected with the Hebrides tranquillized their minds by getting the paupers who disturbed their minds with pity out of their sight, as Abraham got his dead, who disturbed his mind with regret, out of his sight; and there an end. And in the land upon which these "waifs and strays" were thrown out, Government had granted lands gratuitously, or sold them at such low prices, that all men, with or without capital, had become landowners. Capital could not accumulate: there was no fund for the employment of labour: the newcomers had nothing for it but to set to work to wring a scanty pittance from the earth by their own labour. The mischief does not stop here: large tracts of land have been granted to persons who have never looked near them. When these parties find their valuless lands improved by the squatters, they will claim rents that will be refused; then will follow ejectments and riots, such as have been recently witnessed in Prince Edward's Island from the same cause. Thus, between the carelessness of the Hebrides' proprietors and trustees, who, so that they can get their paupers "shovelled out," look no further, and the mismanagement of Government, which has disposed of lands on the worst possible system, and looked on at the progress of a kind of emigration, which must, along with its spendthrift grants, necessarily lead to legal oppression and turbulence, poverty is entailed upon the colony, and a future prepared for it full of agrarian riots. This "shovelling out of paupers" will prove a rare receipt for multiplying Irelands, with their swarms of half-clothed, half-fed, unemployed peasants.

Thatched House,

Howmore, South Uist,Outer Hebrides, Scotland

While the paupers of the Hebrides are a-shovelling out upon Nova Scotia, the paupers of Ireland are being pitchforked into New Brunswick. Two parallel lines of pauper transportation (emigration is an inadequate word) are constantly crowded: the one from the West of Scotland to Nova Scotia, the other from the South of Ireland to New Brunswick. The Government Emigration Agent at St. John's wrote to the Governor on the 1st of July, 1842: "I should have yesterday closed the quarterly accounts of immigration for his Excellency's information, but while doing so the signal was made for a fleet, and I found no less than 13 sail having emigrants on board, which are at anchor off Partridge Island, therefore coming immediately within the quarter ending 30th June. Up to their arrival 5405 had been entered: these arrivals will raise the number to about 7000." These were almost all Irish labourers: a few from Sligo, Belfast; and Dublin, the rest from the country between Cork and Limerick.

On the 28th of June Sir W. M. G. COLEBROOKE wrote to Lord STANLEY, respecting the prospects of immigrant labourers in New Brunswick: "When they arrive it has been found impracticable to discriminate between those who are possessed of any resources, or who may be entirely destitute, and they are indiscriminately thrown on the charity of the country, already overburthened by the destitution arising from general want of employment." How can there be employment for labourers in a country where the manner in which lands have been disposed of has enabled or obliged persons without any capital to become landowners, and has encouraged excessive dispersion over the country?

"A respectable but distressed farmer," in York county is the type of all his class. After a year's residence An the colony he writes: " I have been obliged to send a year-old wether 12 miles to Frederickton and sell it for the trifling sum of 8s. to purchase a few pounds' weight of meal for my family; and since compelled to send a young man two journeys, amounting to more than 40 miles, with 16lb. of butter, which produced only 10s. 4d, to buy a few pounds of flour, which is now made use of. Your petitioner has a good crop in the ground, nearly 30 bushels of seed sown, and 40 bushels of potatoes planted, with an expectation of 25 tons of hay, or more; but it is quite impossible for him ever to secure this crop, unless he can raise the sum of 10 pounds, required for tools, and provisions to support nature." It does not appear that the Irish landlords, or "charitable" associations undertake the "shovelling out paupers" into this country without employment, as is of the case in Scotland; but there is a class of traders in the hopes of the destitute who do the work quite as efficaciously." I was induced," writes a poor Irish emigrant, "from representations and reports which were spread throughout the country, and recommendations to the poorer classes throughout the neighbourhood where I lived, by notices printed in handbills, stuck up in the chapels, and everywhere on the roadside, by a Mr.--, and Messrs-- all merchants of Limerick and owerns of ships for passengers, to come out to this country." This poor man" paid Mr.-- 12 pounds sterling for the passage of himself and his family out;" and thel only means he had of supporting his wife and young children was from a sum of 30s., which was the extent of his pecuniary means when he landed." It ought also to be known, " that among other inducements which Mr.-- held out, was his saying that if they could not "get work in Miramiehi, the Government would give them support, and have them removed to where they could get it at the Government expense;" which was untrue.

It is time that the well-intentioned should desist from this system of "shovelling out paupers," and that Government should interfere to prevent ship-owning crimps from doing it. It is of no avail to send out labourers alone, unless capitalists are encouraged to accompany or precede them. The only legitimate means of promoting the emigration of capital and labour, is by making the place to which they are to emigrate really attractive. This can never be the case with colonies in which all the most favourably situated lands have been granted away, with vague boundaries, to parties who either cannot or will not improve them; in which the land is made a baited trap for squatters to enter on and improve it, in order that when improved some unsuspected owner may arise to snatch it from them. Government is an accomplice in the heartless practice of "shovelling out paupers," so long as it does not take active measures to amend the economical condition of those colonies, or, failing in that, to warn its industrious poor from their inhospitable shores. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are both chartered colonies; and the legislative bodies in both entertain strong prejudices against putting a high price on waste lands, the only means by which capital can be induced to emigrate to them ; and much of the waste lands are, by former improvident grants of the Crown, private property. It is difficult to see how, under these circumstances, the evil can be amended. This is a pity, for the account given of his farming operations by the " respectable but distressed farmer" quoted above, shows what might be made of the country if rightly managed.

Productive herring fishing declined by the 1870s. Poor land combined with poor fishing meant that many of the families in small townships on the island of Lewis were destitute. Representatives from the Royal Commission on the Condition of the Population of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland were sent to interview some of the inhabitants of the Outer Hebrides.

In 1888, conditions in the Outer Hebrides were desperate. There had been a measles epidemic. Although not usually fatal, a number of people, mostly children, died as a result of the epidemic. And though crops had been good, the poor fishing conditions over the previous several years meant that many families were in debt. Stores were not able to extend credit. Had it not been for the good harvest of potatoes and corn on the island, many people would have starved.

1899. World's Fleet. Boston Daily Globe

Lloyds Register of Shipping gives the entire fleet of the world as 28,180 steamers and sailing vessels, with a total tonnage of 27,673,628, of which 39 perent are British.

| Great Britain | 10,990 vessels, total tonnage of 10,792,714 |

| United States | 3,010 vessels, total tonnage of 2,405,887 |

| Norway | 2,528 vessels, tonnage of 1,604,230 |

| Germany | 1,676 vessels, with a tonnage of 2,453,334, in which are included her particularly large ships. |

| Sweden | 1,408 vessels with a tonnage of 643, 527 |

| Italy | 1,150 vessels |

| France | 1,182 vessels |

For Historical Comparison

Top 10 Maritime Nations Ranked by Value (2017)

| Country | # of Vessels | Gross Tonnage (m) |

Total Value (USDbn) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greece | 4,453 | 206.47 | $88.0 |

| 2 | Japan | 4,317 | 150.26 | $79.8 |

| 3 | China | 4,938 | 159.71 | $71.7 |

| 4 | USA | 2,399 | 55.92 | $46.5 |

| 5 | Singapore | 2,662 | 64.03 | $41.7 |

| 6 | Norway | 1,668 | 39.68 | $41.1 |

| 7 | Germany | 2,923 | 81.17 | $30.3 |

| 8 | UK | 883 | 28.78 | $24.3 |

| 9 | Denmark | 1,040 | 36.17 | $23.4 |

| 10 | South Korea | 1,484 | 49.88 | $20.1 |

| Total | 26,767 | 87.21 | $466.9 | |

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.