Central America

Costa Rica ° El Salvador ° Guatemala ° Honduras ° Nicaragua

° Nicaragua Canal

Panama:

° Aspinwall

° Cruces

° The Canal

° Panama Railroad

Nicaragua

° Greytown ° The Nicaragua Canal ° Rio San Juan

The country’s name is derived from Nicarao, chief of the indigenous tribe that lived around present-day Lake Nicaragua during the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Nicaragua has a unique history in that it was the only country in Latin America to be colonized by both the Spanish and the British.

Native Hut. Carib Indian in Doorway. Nicaragua

The discovery of gold in California drew additional attention from American and European powers who wanted to establish and control routes across Panama and Nicaragua. Americans, French and British were among the contenders, and in a move to control a route from the sultry, swampy Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua, the British occupied the Eastern seaboard port of San Juan del Norte between 1848 and 1850, renaming it Greytown.

In 1846, at the beginning of the California Gold Rush, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt established a transit route to facilitate the trip between New York and California.

Transferring from Vanderbilt’s Transit Company steamboats to smaller river- and lake-based steamboats, and covering part of the distance on foot, by mule, or by stagecoach, travelers crossed the isthmus between San Juan del Sur and San Juan del Norte in approximately twenty hours. This innovation cut travel time between East and West Coasts from six months to less than one.

In spite of an extraordinary rainfall (236 inches a year), Cornelius Vanderbilt established a highly profitable route across Nicaragua by waterway and carriage road. In 1851, he developed the route in competition with the Pacific Mail Line, which had joined the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the overland Panama route. The Panama route was laborious until the railroad was completed across the Isthmus in 1855.

San Juan del Sur also played an important role in the conflict between Nicaraguans and U.S. filibusters, first in a local skirmish that resulted in the ouster of Chief Director Laureano Pineda, and later as the site of various battles in the National War against troops led by William Walker. In 1855, San Juan was witness to Walker’s retreat after his June 29 defeat in Rivas; two months later, it served as the arrival point for more filibusters who attacked and took over the city of Granada.

On November 23, 1856 the port hosted the battle between William Walker’s schooner “Granada” and the Costa Rican brigantine “Once de Abril”, and finally on May 5, 1857 San Juan was the scene of Walker’s final retreat on the “St. Mary” after his surrender in Rivas. On December 14, 1856 as Granada was surrounded by 4,000 Honduran, Salvadoran and Guatemalan troops, Charles Frederick Henningsen, one of Walker's generals, ordered his men to set the city ablaze before escaping and fighting their way to Lake Nicaragua. An inscription on a lance reading Aquí fue Granada ("Here was Granada") was left behind at the smoking ruin of the ancient capital city

From Ross, an Australian researcher.

Vanderbilt's route was easier in that once passengers reached San Juan del Norte, on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, most of the journey between the oceans was covered in small boats (bungoes) and steamers. The bungoes ferried passengers and cargo up the San Juan River through 125 miles of jungles filled with howling monkeys and exotic birds, to Lake Nicaragua, then across Lake Nicaragua via steamer to La Virgen (Virgin Bay) near Rivas, Granada on the lake's northwest shore.

The final leg of the journey was atop mules along a precarious eleven-mile path across the isthmus through the jungle to San Juan del Sur referred to as San Juan del Sud during the mid 1800s) on the Pacific Ocean where they met the ships that would take them to San Francisco.

(Editor's Note: A first hand description of this journey and a passenger list from the SS Prometheus was once found in a gold rush diary on the the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild, but the link is now missing. If anyone know of this, please contract us and we will again provide the link as we have received inquiries about the diary.)

Vanderbilt's line was referred to as "The Death Line" because of his inattention to passenger comfort and because of the wreck of his vessels, including the Independence and the North America. However the route proved popular and in the early 1850s, Vanderbilt's line consisted of seven steamers operating scheduled runs that took many thousands of passengers to and from Pacific ports, including San Diego and San Francisco.

Because of the increase in traffic, in 1852, an American Naval frigate, the Cyane cruised Caribbean coastlines to protect American citizens settled in Caribbean ports, including Greytown. On July 13, 1854, the Cyane bombarded and destroyed Greytown when local authorities refused to make reparation or restitution for property stolen from American citizens and for an attack by a mob on the United States consul. Within weeks, news of the controversial bombing was reported around the world, including in the London Illustrated News. In 1855, the Río San Juan changed course and again Greytown was destroyed.

During California's formative years, in addition to transferring passengers and gold, ships laden with all manner of produce from South and Central America reached San Francisco.

Trade was lucrative and a number of agreements were drawn regarding the construction of a transisthmian canal. Contenders included Vanderbilt and U.S. commissions, however, the French made the only serious attempt to develop a waterway across Nicaragua. They began in 1880 and ended in failure in 1889. Panama became the choice and the United States signed a treaty for building a canal across the isthmus in 1903.

December 10, 1849, Tri Weekly Alta California, San Francsico, California, U.S.A.

|

THE HEALTHIEST and PLEASANTEST ROUTE On 24th December the fast-sailing, white oak built ship CLARISSA PERKINS, Captain Goodrich, will be dispatched to Realejo, with passengers for New York, via the lakes of Nicaragua. This route is 1000 miles nearer than by Panama, and avoiding the tropics, passes through a perfectly healthy country abounding in the finest fruits, oranges, pineapples, melons, plantains, bananas, etc., and provisions of every kind. A ride of three days from Realjo through the fine cities of Leon and Grenada, and along the picturesque shores of lakes Leon, Maraya and Nicaragua, brings the passengers to the waters communicating with the Gulf of Mexico. Passengers will be conducted across under the guidance of A.J. Begner, Esq., as interpreter and caterer, and Dr. Donaghe, of New Haven, as physician; these gentlemen having recently arrived from Nicaragua, mules for traveling and all needful accommodations are prepared. A clipper brig will convey passengers from St. Johns, on the Gulf of Mexico, to New York. The trip through is much safer, healthier, more pleasant, and as quick as via Panama. A liberal scale of provisions is adopted by the proprietors of the line. Passage through to New York, including traveling expenses and board in crossing, in the cabin, $275, and in steerage, $220. Passage may be secured by applying to GEO. GORDON, Macondray & Co's., foot of California Street. |

Although the trip was difficult, travelers were captured by the exotic beauty surrounding them as they traveled in bungoes from the Caribbean up the Rio San Juan to Lake Nicaragua.

The jungle trek was the experience of a lifetime. Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) described this river with the words, "And so we started down the broad and beautiful river in the gray down of the balmy summer morning."

Lake Nicaragua is in the middle of a chain of volcanoes that make the area the most striking scenery in Central America. Lake Nicaragua, at one hundred miles long and forty five miles wide, is the largest body of fresh water between Lake Michigan and Lake Titicaca.

August 9, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California

THE NICARAGUA ROUTE.--The means of conveyance by the above named route seems to be now established on a regular and systematic plan. Another steamship will be despatched on the 15th for the point of disembarkation on the Pacific coast, to connect with a fine steamer on the other side. This route is almost entirely by water, a portion through a beautiful and healthy country, and will probably prove the most pleasant for those in haste to reach the States, especially the southern and western portion. See the company's notice in another column.

NICARAGUA ROUTE.--The following advertisement, taken from the New York Courier and Enquirer, must satisfy the public that this quick, cheap and healthy route is complete:

THE NEW AND INDEPENDENT LINE FOR CALIFORNIA VIA NICARAGUA.--The steamship Prometheus will leave Pier No. 2, North River, on Monday, July 14th, for San Juan direct, connecting with the new and elegant steamship Pacific, Captain D.G. Bailey, to leave for San Juan del Sud on the 25th inst. Passengers will take a new iron steamer at San Juan, sent there for the purpose, and pass up the River and across Lake Nicaragua to Virgin Bay, and pass over a good road, 12 miles distant to the Pacific, where the steamship Pacific will be in readiness to receive them. Passengers may secure through tickets at No. 9 Battery Place. Passengers by the line have the preference in crossing from ocean to ocean, by arrangement. All persons going to the East by the line should procure tickets for the GOLD HUNTER and PROMETHEUS. The Gold Hunter will leave on the 15th of August, to connect with the Prometheus on the Atlantic side, direct to New York. For freight or passage, apply to: ISAAC S. SMITH, Agent |

NICARAGUA ROUTE!

VANDERBILT'S INDEPENDENT LINE!

FARE REDUCED!

THROUGH TICKETS TO NEW YORK.

FOR SAN JUAN DEL SUD.

The splendid steamship Gold Hunter, (having been purchased for this route,) will leave for the above port, touching at Acapulco, on Friday, August 15th, at 5 o'clock, P.M., from Pacific Wharf. From San Juan del Sud on the Pacific to Lake Nicaragua there is only twelve miles of Land travel, thorough a most healthy section of country, and on the Lake steamers will be in readiness to convey passengers at once to San Juan de Nicaragua on the Atlantic, where they will find the new and magnificent steamer Prometheus, for New York direct. For freight or passage, apply to ISAAC S. SMITH

PEOPLE'S INDEPENDENT LINE, VIA NICARAGUA The new and splendid double engine steamship MONUMENTAL CITY, Isaac H. Morris, Commander, will be dispatched for San Juan del Sud, touching at Acapulco only, on Friday, 15th August, at 5 P.M., and offers a safe and speedy conveyance to travelers visiting the Atlantic States. Passengers by this steamer will cross the country on the route of the Nicaragua Company, C. Vanderbilt, Esq., President, having only twelve miles of land travel, and will connect at Greytown, with the favorite Atlantic steamship Prometheus, Capt. H.W. Johnson, for New York. Persons intending to go to the Western States will find this the preferably route, as they will thus avoid the Cholera on the Mississippi river. This elegant steamer was built under the supervision of her experienced commander, expressly for this route. She is provided with every comfort, and her accommodations are superior to any other steamer on this coast, her second class passengers occupying state rooms. For passage apply to: RAYMOND, Agent |

Contradictory Views on the Nicaragua Route

August 31, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California, U.S.A.

(Reprinted from The Panama Star of August 11, 1851)

To the Editor of the Panama Star--SIR: Having seen contradictory paragraphs in the several newspapers of this city, in regard to the San Juan route, I take the liberty to give you the facts about the opening trip of the Nicaragua route. I was a passenger on the Prometheus, from New York, July 14th, last. We reached San Juan del Norte on the 23d; left there by the iron steamer Sir Henry L. Bulwer, on the 24th; run about 45 miles up the San Juan river, and came to anchor for the night; next day we ran to the Castillo rapid, and there spent the night. On the 26th, having walked around the portage, (300 yards), we took bungoes, 10 miles, to the Toro rapid, where we got on board the steamer Director, for Virgin Bay; arrived there at daylight, Sunday, 27th, but finding no signal of the arrival of the steamship Pacific at San Juan del Sud, we passed up the Lake, 10 miles, to the city of Rivas, a place of 10,000 inhabitants, where we remained till Thursday, and then came on board the Pacific; left San Juan on Friday, at 2 P.M., and arrived here Monday morning at 2 o'clock -- having made the run in exactly 60 hours. Mules were plenty there, at $5 to $7 each to Rivas, (20 miles), and after we had sent over more than two hundred persons -- as many as 50 mules left the beach empty.

The price from San Juan del Sur to San Juan del Norte, is $40, and not for mules, "for a ride of 12 miles."

Hereafter the ships and boats will meet regularly, and the passengers will pass over the Company's road to Virgin Bay, (12 miles and 18 chains), which it is true, is now only a mule road, but it is being laid with plank, and will soon be a good wagon road.

However, with all the obstacles incident to a first trip, I came from ocean to ocean, in exactly 40 hours running time.

The Company have now three steamers constructing at San Juan, two of which will be placed above Toro rapid, and two below, and the Director for the Lake. Then there will be entire communication from Ocean to Ocean by steam, except a foot passage of 300 yards, and a ride of 12-1/2 miles. That this new route will take a portion of this travel, I doubt not, but that it will destroy the Panama route, I do not believe. There is business enough for all. "Truth is mighty and will prevail." Believing this maxim, I doubt if such an article as that, in this day's Herald, can be of service to any people. I am, "c., your obedient servant,

R.J. VANDEWATER

Panama, August 11, 1851. N.B. -- In reading over again the paragraph of the Herald, I notice the editor says, "We have since learned by persons direct from there," etc. The only persons who passed over the road and back, were Capt. Bailey, Capt. Lucas, Judge Hawes and myself -- all these persons are now here, and the editor must show that one of these made this statement about "nothing to eat or drink and no place to sleep," or take a more unpleasant horn of a dilemma. I left Rivas in the morning, was five hours at San Juan, 20 miles distant; rode back, and took tea at a hotel that would shame all Panama, before dark, the same day. Let that editor "smoke this in his pipe."

San Francisco, August 31, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco

The Nicaragua Route

MESSRS. EDITORS:--A letter signed by R. J. Vandewater, dated Panama, August 11, 1851, was copied in today's Alta from the Panama Star. I feel bound, having unfortunately traveled the route so highly commended by him, to state that Mr. Vandewater is the agent of the line styled "Vanderbilt's Independent Line," and not a passenger, as might be inferred from the letter; that, leaving minor matters aside, Rivas is not situated on the lake, but four miles inland; that the whole province of Rivas hardly contains ten thousand inhabitants; and that "nothing to eat or drink and no place to sleep" were facts, and unfortunately come within the experience of all travelers by that route. Mr. Vandewater himself stated, after his return from San Juan del Sud, that "San Juan was not fit for a dog to stay in," and this is the only one of his assertions I found true.

As to the "twelve mile road," -- that is coming -- and so is Christmas. As to the "hotel at Rivas which shames all Panama" -- it certainly shames the Devil. One more matter: people are not to be gulled now-a-days by "forty running hours;" the time consumed in the transit from point to point was five days, and we were not even encumbered with baggage.

An impression is abroad that the news, fourteen days later, came by the steamer Pacific. This is correct, but it was brought by New York-Chagres passengers across the Isthmus of Panama, who left New York the 28th of July, while all the Nicaragua passengers left New York July 14th, thereby illustrating that the Chagres route is fourteen days the quickest.

I have written this to avoid the misunderstanding arising from the publication of the above mentioned letter and the card of the passengers, in your paper of today. Yours truly,

WM. RABE

General Notice

August 31, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California, U.S.A.

The Vanderbilt Route.-- The passengers by the Prometheus, on the Atlantic side, and on board the steamship Pacific, having met together on the deck of the Pacific when about abreast Monterey, organized by calling the Hon. Geo. W. Wright to the chair, and appointing J. Jones, Secretary.

The chairman having stated to the meeting (which was attended by nearly all the passengers,) the object, which was to inform the community of the wanton breach of faith of the owners and managers of this line, disclaimed to speak as to any matters connected with the management and provisions of the ship, but confined himself to remarks regarding the imposition the passengers had undergone until they came on board this ship.

Upon motion, a committee consisting of Mr. Gass, of Sacramento City, Dr. Rabe, and Mr. Schenck, of San Francisco, was appointed, who reported the annexed resolutions, which were unanimously adopted, and so much as related to general matters and came within the knowledge of the other passengers, met their hearty approbation. The meeting, after being addressed by Dr. Rabe, requested the Committee to report.

Whereas, the persons who have crossed the State of Nicaragua on "Vanderbilt's Independent Line," were induced to take this route, by advertisement from Vanderbilt & Co. by by private letters, and even personal conversation with Mr. Vanderbilt, and his agents, who all promised that passengers would be landed at San Francisco in 25 days after leaving New York; and, Whereas, They were detained nearly double that time, they think it incumbent upon them to put before the community the opinion they were compelled to form of "Vanderbilt's Independent Line for California," and resolve as follows:

Resolved, That the route through Central American possesses natural advantages over the more southern route at Panama, and under proper management, the journey ought certainly to be performed in less than forty-eight days.

Resolved, That the claim of the Vanderbilt Line, or the Ship Canal Co., to the "exclusive" privilege of transit across Central America, is an impudent and barefaced attempt to gull and defraud the public, it being expressly stipulated in their contract with the government of Nicaragua, that their exclusive privileges shall date from the completion and actual opening of the Canal.

Resolved, That the transit charge of forty and fifty dollars demanded of passengers who had been assured by agents at both ends of the route, that the whole expense for passage, with the ordinary amount of baggage, would not exceed twenty-five dollars, was in itself an act of extortion, and that the additional charge of ten cents per pound for baggage was a bare imposition.

Resolved, that the demand by the agents, of toll upon mules belonging to parties who were ready and anxious to take baggage at less than one-fourth the price charged by the Canal Company, would, in a more enlightened country, be called highway robbery.

Resolved, That the contract by which the Vanderbilt Line agreed to receive us on board the steamer Pacific at San Juan, on the 25th July, has been wantonly violated, and no amount of pecuniary compensation can atone for the injury we have suffered by being detained some three weeks among the vermin, filth, and disease of Nicaragua.Resolved, That the conduct of Mr. Vandewater, in waiting for passengers at Panama, was not only in violation of the contract, but a base and shameful violation of his word of honor, pledged as well to ladies as gentlemen, and admits of neither excuse nor explanation.

Resolved, That the combination proposed by Mr. Vandewater, and entered into at Panama, with the agent of the old line, (by which passengers were compelled to pay double the amount which had been charged on many previous occasions,) ought to throw discredit and disgrace on any line professing to run as an independent opposition.Resolved, That the threat of remaining still longer at Panama, to take passengers of need be at $50, (which threat was used by Mr. Vandewater to compel the agent of the old line to increase his prices,) imposed a hardship upon persons who were awaiting passage at Panama, while it inflicted a wrong upon those who crossed at Nicaragua, under promise that the fare upon the Pacific side should be as low as the lowest charged from Panama.

Resolved, That we have but little confidence in the integrity and honor of parties connected with the "Vanderbilt Line," and none at all in their general agent, Mr. Vandewater; and we advise all parties who may be so unfortunate as to be brought into business contact with either to guard themselves by written contract.

Resolved, That we recognize in Capt. Lucas the skillful mariner, the able commander, and the perfect gentleman.

Resolved, That the passengers generally, and the ladies in particular, feel under especial obligations to Capt. Bailey for the untiring exertions he has used to render the voyage both comfortable and pleasant.

Resolved, Last, though not least, that the California, Isthmus, and United States papers generally, be requested to publish these proceedings pro bono publico.

(Signed)

W.M. RABE, M.D. WM. GASS,

of Sacramento City

J.W. SCHENCK, of San Francisco au31-1*

Daily Alta California, September 18, 1851

The Nicaragua

As there have been many conflicting rumors and statements in relation to this route, a mercantile firm in this city has placed in our hands, for publication, the following extract from a letter from a gentleman who left San Francisco in the steamer Independence, July 31, 1851, dated--

SAN JUAN DE NICARAGUA, Aug. 22d, 1851

We reached San Juan del Sud on the 16th, at noon. The harbor is quite small, say one mile deep/ width of basin about the same; entranc about half a mile across. A south wester would make fearful work among the shipping, but from all I can learn here, none are to be apprehended. The beach resembles that at Taboga more than any place I have seen. There are some six or eight good sized Ranchos at this place, all well provided with hammocks; and poultry, eggs, plantains, &c., are abundant. Soon after we dropped anchor, the Hon. Mr. Wright and Dr. Rabe came on board and gave us welcome information that the route was open, and that about two hundred of the passengers by the Pacific had gone over, and had reached New York, it was supposed, in 28-1/2 days from San Francisco.

Upon going ashore, we learned from Mr. Horn, the Forwarding Agent, that the rate of transmission was $40 for those not holding through tickets, and $30 for those holding through tickets; or through cabin tickets to New York, $130, and ten cents per pound for baggage. The passengers, thinking the charge of $40 exorbitant, especially so, as all the New Orleans passengers (who could not obtain through tickets), would thus pay more for their transmission than those bound to New York, held a meeting on board the steamer, and a committee was appointed to wait upon Mr. Horn, and inform him that they were determined to pay no more than $25. The result was that $25, and 5 cents per pound for baggage was charged to each passenger.

At daylight of the 17th the passengers commenced their disembarkation, and as soon as possible obtained their mules and set forward. The company have an abundance of horses and mules, which are easily kept here, and are cheap, say $15 each. Great delay was occasioned by the weighing of baggage, obtaining checks to be posted upon each package and getting receipts for the amount of transportation.

At about nine o'clock our party got started for Virgin Bay, twelve miles distant, which we reached at 2 P.M. The first four miles of the road leads through the woods, and is the only bad portion of it. There are several hills (none however of much magnitude) to ascent, and in many places the mud is some six or eight inches deep; and there are two or three shallow streams to cross of about six or eight feet in width. The next four or five miles runs through a fine undulating country, with occasionally a copse of trees or bushes, well sodded, and a good hard road. The remainder of the road is through a level country much of it marshy, obliging us to walk our mules, but they got through without the least inconvenience. There is but one ranch on the road and but scantily supplied with eatables. The only safe plan is to lay in a stock of provisions before starting.

The settlement at Virgin Bay consists of six or eight ranches, pretty well supplied with hammocks and provisions. I should judge it to be a healthy place. The steamer Director lay out a quarter of a mile from the shore, and we took passage in a large bungo, to reach her. The bungo not being able to come close to the shore, ourselves and baggage were carried on the backs of the natives to her. The baggage went safe, but some of the passengers got thrown off, and were well soaked. About four hours were occupied in getting us off, and at 10 o'clock we got underway.

There were about two hundred of us on board, and we found ourselves very much crowded, especially as it commenced raining at this time (the first during the day) and those on the upper deck were compelled to take shelter on the main deck. The Directoris of 30 horsepower, and I should think she would comfortably accommodate 150 persons. No meals were furnished on board this boat.

From Virgin Bay we took a south easterly course to San Carlos, about 60 miles distant, where we entered the San Juan river. This point we reached at 8 o'clock A.M., and proceeded down the river 25 miles, where we left the steamer and took the bungos, or native dug-outs. These are very large, and carried from 18 to 20 passengers, with their baggage. We took these boats at 1 P.M., and at 6 found ourselves alongside the steamer Sir Henry Bulwer. The distance run in the bungos was 22 miles, and we crossed three rapids. The first is named Toro, and is 10 miles down from where we left theDirector. I understand it is the intention of the company to have the steamer in future come down to this rapid. This rapid is much the larger of the three, but is not, in my opinion, as bad as several on the Chagres river, and we got through it without the least trouble. The second rapid bears the name of Castillo Viejo - old castle - a fort, standing on the shore, and the rapid is supposed to have been made by the Spaniards throwing stores and munitions in here at the time of Lord Nelson's attack upon the country; it is certain he was not able to pass this point. The third rapid is called Machuca, and here lies the ill-fated steamer Orus, hard aground, but apparently in sound condition.

The steamer Sir Henry Bulwer is a two-decked boat, with an awning over the upper deck, and capable of offering sleeping accommodations, by stretching out on the deck, for 180 people. The main deck is pretty much taken up with the engine, fire-room, baggage &c. She is a stern-wheel boat, and somewhat resembles the Gov. Dana, excepting as being a superior boat. She has two 10-inch cylinders and 3 feet stroke.

Here also nothing could be had to eat, excepting one biscuit apiece, and the passengers began to be riotous; but some provident ones having supplied themselves, a division was made, and we lay down to sleep.

At 3 o'clock next morning, Tuesday, 19th August, the boat got up steam, and reached San Juan de Nicaragua, 60 miles run, at noon. We were much disappointed to find no other steamer here than the Avon, an English vessel, for Chagres. We all found good accommodations at $1.50 per day, and are now impatiently awaiting the arrival of the Prometheus.

The river is of an average width of say 1-2 mile: it is much more straight than the Chagres; the scenery, perhaps not quite so romantic. As to the healthiness of the country, that from the Pacific to the Lake, and along the shores of the Lake, I should think must be decidedly so, from its general features. As we approach the Atlantic, however, it becomes low and must be taken as a place for fever. This place is considered healthy; there are some few cases of fever, but all of our passengers, so far as I know, are in good health, excepting the carpenter of the Independence, who was sick on board.

You will perceive that we were just fifty one hours making the crossing, and that the distance is 182 miles. It is the general opinion that the route is far preferably to that of Panama, and when they have more boats, as they expect to immediately, (I understand another goes on this week) and give something to eat on board, it will be the route. Some 60 of the passengers hired mules at San Juan at $5 each for Virgin Bay, there took a schooner and bungos to this place for $10; had plenty to eat and got through in 4-1/2 days. The British steamer Avon took about 50 of our passengers to Chagres at $15, mostly those bound to New Orleans, and a schooner has since left here for New Orleans with some 30 or 40 on board.

Vanderbilt has missed it, having no boat here, and I fear the Oregon's passengers will head us. There is an English man-of-war in the harbor, and several square-rigged vessels, sloops and schooners.

The Prometheus arrived at San Juan de Nicaragua from Chagres, 24th Aug.

September 3, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California

Nicaragua

MESSRS. EDITORS: The Evening Picayune of September 1st, contained at editorial article, which, in a mild manner, tried to exculpate Vanderbilt's line from the effects of the passengers' card, published in the Alta on Sunday, and your paper of yesterday contained a communication signed by Harris T. Fitch, whose misstatement and aspersions of my character, too favorably known to suffer by such insinuations, make it incumbent upon me to answer, which I now intend to do, by giving a description of the trip.

In positive contradiction of Mr. Fitch's letter, I first say, that the complimentary resolutions to thePrometheus were given to the purser of the ship at San Juan de Nicaragua, and were not written at Rivas; that Mr. George Wright, or member of Congress, presided at both of the meetings, both on the Prometheus and Pacific; that no complaint whatever has been made by me regarding the passage on the Atlantic side; farther, that Mr. Fitch did not stay long at Rivas and the shed called San Juan del Sud, but went with Mr. Vandewater to Panama and back again, on business, as I understand, of the company, and that consequently he did not participate in our main sufferings, that is, the protracted stay at Rivas, and on the sea shore. I also say distinctly, that the meeting where the card was adopted was held on the deck of the Pacific, Mr. Wright again presiding; that every publicity possible was given, the bell being rung throughout the whole ship, and passengers invited to attend; that Mr. Fitch himself attended; that he only made one objection to one of the resolutions, which was altered to suit him, and that the whole was unanimously passed, as reported by the chairman and secretary afterwards.

I do not know what interest Mr. Fitch has, if any, direct or indirect, in this line, and whatever may be Mr. Fitch's experience or notions of comfort, he ought to know that it entirely depends upon what persons are used to. As to the discovery of my not having paid the passage money, I suppose, that the people of San Francisco know enough of Dr. Rabe and the usual management on board the steamers to know that no discovery could be had in this case, and I certainly had paid my passage on the Atlantic, and paid two hundred dollars on the Pacific, and would be beholding to them for board, which I also paid. But so much in vindication of me, and the description of the trip will settle the hash.

I had only been in the States about twelve days when I heard of the disastrous May fire, by which I was, as many others, a heavy sufferer; and although anxious to stay with my children as long as possible, I conceived that I should immediately return. The Vanderbilt line was then the rage; but being rather doubtful about their newspaper puffs, I took the extraordinary precaution to write to Mr. Vanderbilt from Philadelphia, and a copy of the answer is to be found below. In due time I took a ticket at the office for San Juan on the Atlantic, for which I paid fifty dollars, (some paid fifty, some seventy, some even one hundred, and a few forty-five dollars, for first cabin passage!)

On board I found Mr. Wright, his lady and child, and Mr. Vanderbilt himself. Mr. Wright, as well as myself, expressed in each other's presence to Mr. Vanderbilt, our necessity and desire to go straight and quick through, and that we would go to Chagres if there was any possibility of unusual detention or hardship. Mr. Vanderbilt said that we would get through before any other passengers who had started about the same time for California, insisted upon our going, and tendered us a free passage, and we went on.

We had been ten days from New York; on the eleventh we went on board the famous iron steamer. We had gone about half a mile, when she struck; the passengers animated with a laudable desire, with the exception of a few, jumped into the water, and after three hours' hard labor to drag her over, trying to lift her up, or pull her along, they were exhausted and "gave up ship;" when the captain of an English man-of-war, fortunately in the harbor, gallantly came to our assistance with a part of his crew, and after renewed exertions of all we got over it, and five running hours were consumed in going one mile. On we went.

During the night there were no accommodations for sleeping, not a single berth; the room styled the cabin, pretty well filled with baggage, was occupied by the ladies as best they might, and the gentlemen picked out the softest plank on deck and laid down. No cooking stove being on board, we, of course, fared accordingly. Second day, being the day after passing one rapid successfully, we came to a halt at another. During the whole evening Mr. Vanderbilt tried unsuccessfully to get the board over, and on the third day, having spent a miserable night under the same privations, we were packed in bungies, each man squeezing himself in the best way he could, in good old Chagres river-fashion. We went our way rejoicing, consuming nearly the whole day in going nine miles, against an immense strong current - a good rain coming down bountifully upon us "kept us cool."

That evening we got on board the steamer Director, on which we left for the lake, which we entered, as well as memory serves me, at dusk. To my astonishment I found the lake a boisterous expanse of water, running as high as the angry Atlantic. The steamer Director had no cabin, but is a thing similar to our tug-boat. The ladies made a screen on deck of blankets, the rest of the passengers laid down on deck. But the water washing over us continually, made us get up pretty soon, and between sea-sickness, previous hunger, cold, wet and fatigue, we had a pretty night of it. Next morning we hove in sight of the shore, where a red flag was stuck up, and cast anchor a few hundred yards off shore. Mr. Vanderbilt went ashore, intending, as he said, to see us landed. On the beach we saw him mount a horse, and we had the pleasure of seeing him again that evening at that famous hotel at Rivas.

Up and down went the steamer, the surf beat ashore with fury, and after lying an hour or more, a large pungy or canoe left the shore, apparently to take us off, but turning over in the surf, it spilled the natives. They swam to the shore, and made no further attempt to land us from that quarter. Two or three hours more we waited, when we concluded we would land in the steamer's boat; and going in to the shore stern foremost, we all ultimately landed, some getting wet all over, some partly, and one, Mr. E.L. White, being carried ashore by a native who spilled him, got a handsome ducking. At that shore there was no house, and after waiting some time, some took horses and others walked into the town of Rivas, situated about four miles from the lake, inland.

This town is a small settlement, containing probably fifty or a hundred houses, built low, and encircling immense yards, one building occupying about as much space as the square bounded by Clay, Montgomery, and Commercial streets. It is true that the lying natives talked about ten thousand inhabitants, but the whole province of Rivas, being one of the seven of the Republic, does not, in fact, probably contain as many.

There we staid four days, at two dollars a day, on pretty good fare. In the meantime, the Pacific had arrived at the Pacific coast, with four hundred and twenty five passengers. The Prometheushad gone to Chagres. The passengers being informed of the price of forty dollars for transit, ten cents per pound for baggage, of the want of provisions on the route - there being but one shed from San Juan de Nicaragua to Rivas - refused to go - they having the option to land at San Juan or at Panama. One hundred and fifty ultimately came over, and they may describe their hardships themselves. At any rate, I understood from responsible sources, that great disturbances took place on the lake as well as the river. From this time begins our positive right to complain. It was there where we stuck again, and to that and the subsequent conduct of Vanderbilt and Vandewater, that this card is owing.

Vandewater promised to return on the 10th of August, and offered to pay our board in the meantime at Rivas. After he had left, he sent word by Captain Baldwin that he could not be back before the 13th, but would be there certain, then. Our board became immediately so miserable that the passengers requested me to attend to the matter, when we found out that Mr. Vandewater had accorded our board for one dollar and a quarter, from the time he assume the payment; and the landlord very properly observed that he was bound to reduce his expenditures. The hotel was kept by an English ex-captain of dragoons, and a faint idea might be formed by travelers, of the cookery under his direction, executed by indolent natives. On the 12th we started for San Juan del Sud, about twenty miles from Rivas - a road pleasant enough in dry weather, but horrible when wet; some took one, some two days to go. At the shed in San Juan del Sud, we staid three days after the time appointed. On the 16th, the steamer came, being twenty-one days later than promised in the subjoined letter. The accommodations, or in fact the want of them, on the steamer, beggars all description. I have been on the Pacific sea six times; never saw the like in my life, any where.

Passengers were some paying $200 to $250 passage money. The potatoes gave out in three days; no fresh bread; the ship's biscuit was old, rotten and wormy, and was put in the oven every day to drive out and kill the insects; the fish stunk; the oranges instead of coming to the table, wee sold at the bar for 12-1/2 cents per piece; soda water at fifty cents a glass. The price of wines, which were abominable, was raised during the passage, as Mr. Fitch knows; and we were advised, under the direction of Mr. Vandewater, who had assumed a full sway on board the ship, interfering with every thing, that we must buy sugar at the bar, if we wanted to make lemonade. At Acapulco no beef was taken in, there being still some half-dead cows on board, whose natural end was only anticipated by the butcher a day or two. Eight dozen chickens were laid in there, and when within three days from this port, matters and things became so woeful that nothing but the fact of a passenger having three dozen chickens as freight on board saved us from positive starvation. The firemen were in perfect uproar; they took, in the night, a pig killed for the passengers, a turkey which had found its way there, and some chickens; and nothing but the extraordinary exertions of Capt. Lucas, with whom we all sympathized in his trying condition, got the ship on.

I further state, upon the authority of Capt. Lucas and the head steward, that the necessary requisition had been made in Panama, and that Mr. Vandewater had only bought a small part of it. I also must again mention, that the passage money exacted from passengers at San Juan was as great, and in many instances greater than that paid by the passengers at Panama; and Vandewater himself forced the other line to raise the price. Suffice it to say, we are here, thank God! I have other business to do than to write letters of this kind, but am willing and ready, if it should be to the interest of the community, and if requested by a respectable party, to give a more public and full exposition of the gross and wanton frauds imposed upon us on the route; but I hope that no more of the employees or persons interested, directly or indirectly, in the welfare of the company, will make themselves notorious by aspersions on my character and motives, which I believe my character here does not warrant.

WM. RABE

P.S. Probably Mr. Fitch knows that I was presented by Mr. Vanderbilt with a free passage on the Pacific, and when it was found out that I would not suffer the community to be imposed upon, passage money was demanded of me, and paid by me.

September 18, 1851, Daily Alta California, San Francisco, California

The Nicaragua Route -- We find the following notice of the new Line among the remarks of the N. Y. Herald on the arrival of the Prometheus:

"The facts stated by our correspondents on the subject, whose letters we publish this morning, present a very clear and interesting statement of an actual experiment; from which we think it may be safely assumed that the trip between New York and San Francisco, by the Nicaragua route, will yet be accomplished in twenty-two or three days. The shortest trip, we believe, ever made by the Panama route, was thirty-one days. The trip by the Nicaragua has actually accomplished it in twenty-nine; and several days yet may be saved in perfecting the transit of the isthmus."

Traveller's Travails

January 15, 1852, Alta California, San Francisco, California

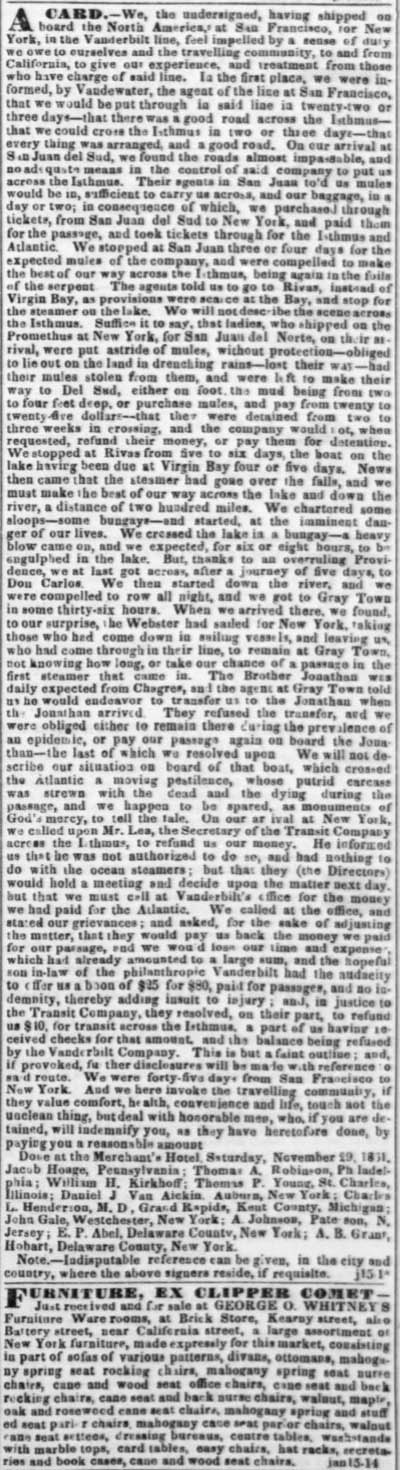

A CARD.-- We, the undersigned, having shipped on board the North America at San Francisco for New York, in the Vanderbilt line, feel impelled by a sense of duty we owe to ourselves and the travelling community, to and from California, to give our experience, and treatment from those who have charge of said line. In the first place, we were informed, by Vandewater, the agent of the line at San Francisco, that we would be put through in said line in twenty-two or three days - that there was a good road across the Isthmus - that we could cross the Isthmus in two or three days - that everything was arranged and a good road.

San Juan del Sud, we found the roads almost impassable, and no adequate means in the control of said company to put us across the Isthmus. Their agents at San Juan told us mules would be in, sufficient to carry us across, and our baggage, in a day or two; in consequence of which, we purchased through tickets, from San Juan del Sud to New York, and paid them for the passage, and took tickets through for the Isthmus and Atlantic. We stopped at San Juan three or four days for the expected mules of the company and were compelled to make the best of our way across the Isthmus, being again in the foils of the serpent. The agents told us to go to Rivas, instead of Virgin Bay, as provisions were scarce at the Bay, and stop for the steamer on the lake. We will not describe the scene across the Isthmus.

Suffice it to say, that ladies, who shipped on the Prometheus at New York for San Juan del Norte, on their arrival, were put astride of mules, without protection - obliged to lie out on the land in drenching rain - lost their way - had their mules stolen from them, and were left to make their way to Del Sud, either on foot, the mud being from two to four feet deep, or purchase mules, and pay from twenty to twenty-five dollars - that they were detained from two to three weeks in crossing, and the company would not, when requested, refund their money, or pay them for detention. We stopped at Rivas from five to six days, the boat on the lake having been due at Virgin Bay four or five days. News them came that the steamer and gone over the falls, and we must make the best of our way across the lake and down the river, a distance of two hundred miles. We chartered some sloops - some bungays - and started, at the imminent danger of our lives. We crossed the lake in a bungay - a heavy blow came on, and we expected, for six or eight hours, to be engulphed in the lake. But, thanks to an overruling Providence, we at least got across, after a journey of five days, to Don Carlos. We then started down the river, and we were compelled to row all night, and we got to Gray Town in some thirty-six hours.

When we arrived there, we found to our surprise, the Webster had sailed for New York, taking those who had come down in sailing vessels, and leaving us, who had come through in their line, to remain at Gray Town, not knowing how long, or take our chance of a passage in the first steamer that came in.

The Brother Jonathan was daily expected from Chagres, and the agent at Gray Town told us he would endeavor to transfer us to the Jonathan when the Jonathan arrived. They refused the transfer, and we were obliged either to remain there during the prevalence of an epidemic, or pay our passage again on board the Jonathan - the last of which we resolve upon. We will not describe our situation on board of that boat, which crossed the Atlantic a moving pestilence, whose putrid carcass was strewn with the dead and the dying during the passage, and we happen to be spared, as monuments of God's mercy, to tell the tale.

On our arrival at New York, we called upon Mr. Lien, the Secretary of the Transit Company across the Isthmus, to refund us or money. He informed us that he was not authorized to do so, and had nothing to do with the ocean steamers; but that they (the Directors) would hold a meeting and decide upon the matter next day, but that we must call at Vanderbilt's office for the money we had paid for the Atlantic. We called at the office, and stated our grievances; and asked, for the sake of adjusting the matter, that they would pay us back the money we paid for our passage, and we would lose our time and expenses, which had already amounted to a large sum, and the hopeful son-in-law of the philanthropic Vanderbilt had the audacity to offer us a base of $25 for $80, paid for passages, and no indemnity; thereby adding insult to injury; and, in justice to the Transit Company, they resolved, on their part, to refund us $10, for transit across the Isthmus, a part of us having issued checks for that amount, and the balance being refused by the Vanderbilt Company. This is but a faint outline; and, if provoked, further disclosures will be made with reference to said route. We were fort-five days from San Francisco to New York. And we here invoke the travelling community, if they value comfort, health, convenience and life, touch not the unclean thing, but deal with honorable men, who, if you are detained, will indemnify you, as they have heretofore done, by paying you a reasonable amount.

Done at the Merchant's Hotel, Saturday, November 29, 1851. Jacob Hoage, Pennsylvania; Thomas A. Robinson, Philadelphia; William H. Kirkhoff; Thomas P. Young, St. Charles, Illinois; Daniel J. Van Aickin, Auburn, New York; Charles L. Henderson, M.D., Grand Rapids, Kent County, Michigan; John Gale, Westchester, New York; A. Johnson, Paterson, New Jersey; E.P. Abel, Delaware County, New York; A. B. Grant, Hobart, Delaware County, New York.

Note:--Indisputable reference can be given, in the city and country, where the above signers reside, if requisite.

January 10, 1856, Daily Alta California, San Francisco

NICARAGUA AND ITS PEOPLE.

Nicaragua contains about 49,000 square miles. Its population is estimated at 247,000, of which by far the largest portion are females. Not more than 20,000 of the people are whites, the rest being Indians, Negroes, and mixed races.

January 31, 1856, Sacramento Daily Union, Sacramento, California, U.S.A.

The Lake of Masaya.

Last week, in company with a few friends, we made a visit to the famous Lake of Masaya. Rising early and fortifying ourselves with a cup of strong coffee, we left our posada near the plaza of Masay, and proceeded on foot towards the lake. It is about half a mile distant from the plaza. We had no difficulty in finding the road, for there is a constant stream of water carriers parsing to and fro, between the lake and the town, from morning to night, and we at once fell into the current. Our road lay through a long and thinly populated street, where only here and there a foliage-embowered hut suggested ideas of rural felicity, until it terminated in the open country; and, lo! the descent to the lake. Before we saw its placid bosom, we gazed on the narrow winding path that led to it; it was so steep in some places as to be almost perpendicular, and resembled, from the small, loose rocks lying intermingled with the large fixed ones, the dry bed of a mountain torrent. A dense tropical forest, through which the rays of the morning sun did not penetrate, hemmed it in on either side. We thought, as we looked, of the horrible superstitions which had once prevailed about this very spot, and reflecting upon the character and habits of the race, it seemed but natural enough. But when we saw the women and children toiling, with cheerful faces and gleeful voices, up and down the precipitous road, laden with their water jars, "dripping with coolness," there was such an air of life, amd health, and genial homeliness about the scene, as to dispel at once our darker reminiscences. We commenced the descent, and rough as was the way, we were constantly rewarded for our pains, by the fresh beauties which the landscape presented at every turn.

Through piled masses of bloom and greenery, taking every form of vegetable architecture, we saw the lake asleep in the early sunlight. Often a native woman or child would direct our steps; the road that we had literally to crawl over in places, they had traveled for years, and stepped from rock to rock with the self-confident tread of a chamoise-hunter. There was nothing grander or wilder in the Scottish hills, or encircling the Scottish lakes; oh! for a shielding here, with the enduring hills around, and the misty mountain wind, so free, to blow upon us. How old Kit North would have shouted for joy, to traverse this pith. In all of his pictures of "Kit in the mountain,'' he gives us nothing like to this. The solitary beauty of this sunken lake, as it seemed, the grandeur of the accessories to the picture, including the volano of Masaya, from the crater of which dense masses of white smoke were sluggishly rising heavenward, the primeval forest on either hand, all evidences and tokens of the everlasting summer which here reigned supreme, made up a panorama which "it were worth while coming all the way from old Reekie to see."

This stormy aspect of the landscape changed as we approached the level of the lake. Here we saw the blue hare-bells and the white-jessamine, emblems of peace and hope; and many another well known and familiar flower, growing side by side with those we had never seen before, while the more open character of the forest gave us a clearer view of the lake and the broad fields beyond. At length, after a tramp of some twenty minutes, we were seated upon a huge rocky promontory on the shore of the lake. We forgot to say that one of our party ignoininiously deserted us, when about halfway down, and the last we saw of him be was standing upon a sharp bend in the road, with a lugubriously ridiculous countenance, muttering something about "Facilis decensus Averni," or words to that effect. The unhappy man — but we forbear, for he is still our friend.

Sitting upon the shore, and looking back and upwards to the path we had traveled, we saw the Indian girls threading their way through the overhanging forest, and as they appeared and disappeared through the interstices of the thick wood, bending beneath their load as they toiled upward, but springing along with fawn-like fleetness, in their descent, the scene wad singularly suggestive. We knew not the history of the city of Masaya, but we wondered within ourselves if it had been always so — if this people from the beginning had been wont to travel this toilsome pathway — and, if so, what need to have built it there, when the land was full of mountain streams?

Was it chance, or the mysterious anger of Providence that ordained it? or did some convulsion of old mother earth swallow up her well-springs and force her people to the hard necessity of coming daily all this long, weary way for a supply of that element which bubbles up spontaneously at the door of every poor cottage on the hills.

If so, what a terrible day it was for then when they first found themselves chained to this necessity for life; but with the lapse of time they became used to it, and to-day this labor is, perchance, as requisite to their health and comfort as their daily meals.

Once fairly down, there was, of course, nothing for it but a bath — and such a bath; those of our readers who have the felicity of knowing Capt. Bunsby will understand what we would say when we tell them that "it was a bath as was a bath." The glorious sensations we experienced on emerging and rubbing down were such as to make us converts to the hydropathic system. And why not have a hydropathic institution on the iborea of this grandly beautiful lake? Why should not our friends at the North have a Southern watering place, where they may pass away the dreary winter season in a land lovely as "the garden which the Almighty planted eastward in Eden?" They will come. The time has arrived when the half-prophetic remarks of Stevens, written in allusion to a neighboring locality, even within sight of where we sat, will be realized. And with this quotation we cose this rambling article:

"Impressed," he says, " with the solitude and the extraordinary features of a scene upon which so few human eyes have ever rested, and the power of the Great Architect, who has scattered his wonderful works over the whole face of the earth, I could not but reflect upon what a waste of the bounties of Providence in this favored but miserable land. At home, this volcano would be a fortune, with a good hotel on top, a railing round to keep children from falling in, a zig-zag staircase down the sides, a glass of iced lemonade at the bottom. Cataracts are good property with people who know how to turn them to account. Niagara and Trenton Falls pay well, and the owners of volcanoes in Central America might make money out of them by furnishing facilities to travelers." And in another connection he observes: " To men ol leisure and fortune, jaded with rambling over the ruin" of the Old World, a new country will be opened. After a journey on the Nile, a day in Petra, and a bath in the Euphrates, English and American travelers will be bitten by mosquitoes on the Lake of Nicaragua, and drink champagne and Burton ale on the desolate shores of San Juan on the Pacific."

Let them come. Ours is a great country, and there is room for all.

Greytown

During the 19th century, the Caribbean coast town of San Juan del Norte was a prosperous community inhabited by Spanish and Nicaraguans. However in 1841, the British invaded and eventually renamed it Greytown, in honor of then-governor of Jamaica, Sir Charles Grey. Located almost at the mouth of the San Juan de Nicaragua River, Greytown's tumultuous history includes serving as a hub along the Central American route to the California Gold Rush. In the 1850’s, gold-seekers looking for a faster route to California than across North America by stage coach, would take a ship from New York to Greytown, then board a boat up the San Juan River and cross Lake Nicaragua.

Lake Nicaragua, with an area of 3,149 square miles (8,157 square km), is the largest lake in Central America. The lake is bisected by a chain of volcanos which has led to the formation of numerous islands, the largest of which is Ometepe Island.

From the western shore of Lake Nicaragua they would go by mule the few kilometers to San Juan del Sur, a port on Nicaragua’s Pacific Coast. There, Clipper ships and steamships would be waiting to take them north to San Francisco and the gold fields of the Sierras. The history includes an unsuccessful attempt to build an inter-ocean canal, long before the Panama Canal was constructed.

Rio San Juan

The San Juan River is a timeless passageway through dense tropical rain forest from Central America's grandest lake to the Caribbean Sea. This historic river was the stage for great colonial period battles between the Spanish Crown and British and French pirates and later became the route of Cornelius Vanderbilt's inter-oceanic steam ship service during the California gold rush. The 190 km length of the Rio San Juan was described by Mark Twain as "an earthly paradise" from the inland sea of Lake Nicaragua to the Caribbean with more than 4,000 square kilometers of virgin rainforest and wildlife. The Indio River runs into the heart of the rain forest, home to many species: howler, white faced and spider monkeys, jaguar, giant anteaters, crocodiles, toucans, parrots and a rainbow of orchid and butterflies. Over 600 species of birds live there, along with more than 300 species of reptiles and 200 species of mammals. It is the biggest expanse of lowland rain forest north of the Amazon basin.

1899. World's Fleet. Boston Daily Globe

Lloyds Register of Shipping gives the entire fleet of the world as 28,180 steamers and sailing vessels, with a total tonnage of 27,673,628, of which 39 perent are British.

Great Britain 10,990 vessels, total tonnage of 10,792,714 United States 3,010 vessels, total tonnage of 2,405,887 Norway 2,528 vessels, tonnage of 1,604,230 Germany 1,676 vessels, with a tonnage of 2,453,334, in which are included her particularly large ships. Sweden 1,408 vessels with a tonnage of 643, 527 Italy 1,150 vessels France 1,182 vessels For Historical Comparison

Top 10 Maritime Nations Ranked by Value (2017)

Country # of Vessels Gross

Tonnage

(m)

Total

Value

(USDbn)

1 Greece 4,453 206.47 $88.0 2 Japan 4,317 150.26 $79.8 3 China 4,938 159.71 $71.7 4 USA 2,399 55.92 $46.5 5 Singapore 2,662 64.03 $41.7 6 Norway 1,668 39.68 $41.1 7 Germany 2,923 81.17 $30.3 8 UK 883 28.78 $24.3 9 Denmark 1,040 36.17 $23.4 10 South Korea 1,484 49.88 $20.1 Total 26,767 87.21 $466.9

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.