Louisiana

° New Orleans ° The Mississippi Bubble

New Orleans

The Port of New Orleans has been at the epicenter of American history for centuries: Wars were fought over it, and Louisiana was purchased by the United States in order to obtain New Orleans.

Map depicting plantations on the Mississippi River

From 1718 until 1810, New Orleans was essentially European. Decreed a city at its founding by Bienville in 1718, New Orleans was laid out by the French engineer, Adrien de Pauger, in a classic eighteenth-century symmetrical gridiron pattern, but the streets were little more than muddy ruts.آ

It did not really matter at the time as there were insufficient people to fill the grid until 1800.آ

From the beginning, New Orleans had a reputation as a very important place; and for most of the eighteenth century, image was more important that reality. Although its geographical situation, strategically important site, and master plan for development guaranteed New Orleans a bright future, the realization of that promise was dependent upon the ambitions of the dominant political powers of the day.

Like so many American cities, promise and growth depended upon which political power controlled the interior of North America. In the eighteenth century, three European powers, France, Spain, and Britain were rivals for dominance.آ

Oddly, it was France's economic policy of regulating all mercantilism to the benefit of the state, that held back the growth of New Orleans. Odd, because America's growth at that time depended on sea trade. The French viewed Louisiana and the Mississippi Valley as a buffer against British expansion westward from their seaboard colonies and, so, saw no point in investing large sums in Louisiana, except for the brief period from 1716-1722, that saw the founding of New Orleans.

John Law, a Scotsman, gambler, and financial advisor to the Duc d'Orleans, developed a scheme to form the Mississippi Company to assume the French Crown's debt in return for a charter to operate Louisiana as a colony. Law's ingenious proposal called for the proceeds from the sale of shares in the Mississippi Company to the French public to be used to back the Crown's debt and currency. Shareholders would receive dividends on the profits the Mississippi Company would reap.

1719-1720: MISSISSIPPI BUBBLE

John Law and the French Mississippi Company

By the time of Louis XIV’s death in 1715, the treasury was in shambles, with the value of metallic currency fluctuating wildly. The following year, the French regent turned to a Scotsman named John Law for help. Law, a gambler who had been forced into exile in France as the result of a duel, suggested the Banque Royale take deposits and issue banknotes payable in the value of the metallic currency at the time the banknotes were issued.

Law’s strategy helped the French convert from metallic to paper currency, and resulted in a period of financial stability.

In August 1717, Law incorporated the Companie des Indes (commonly known as the Mississippi Company), to which the French regent gave a monopoly on trading rights with French colonies, including what was then known as “French Louisiana.” In August 1719, Law devised a scheme in which the Mississippi Company subsumed the entire French national debt, and launched a plan whereby portions of the debt would be exchanged for shares in the company. Based upon the expected riches from the trading monopoly, Law promised 120 percent profit for shareholders, and there were at least 300,000 applicants for the 50,000 shares offered.

As the demand for shares continued to rise, the Banque Royale which was owned by the French government but effectively controlled by Law continued to print paper banknotes, causing inflation to soar. The bubble burst in May 1720 when a run on the Banque Royale forced the government to acknowledge that the amount of metallic currency in the country was not quite equal to half the total amount of paper currency in circulation. On May 21, the government issued an edict that would gradually depreciate Mississippi Company shares, so that by the end of the year they would be valued at half their nominal worth. The public outcry was such that one week later, on May 27, the Regent’s Council issued another edict restoring the shares to their original value. On the same day, however, the Banque Royale stopped payment in specie. When the Banque Royale reopened in June, the bank runs continued. By November, shares in the Mississippi Company were worthless, the company was eventually divested of its remaining assets, and Law was forced to flee the country.

The Evening Post,آ London, England: From Thursday September 21 to Saturday September 23, 1721

September 30,آ The Amsterdam Courant, Hanover September 23.

The famous John Law arrived here Incognito last Thursday with his Son, and was since Treated by divers Persons of Distinction; The Saturday following he had the Honour of being introduced to Prince Frederick, he is since gone for England if the common Report is true.

The Evening Post,آ London, England: From Saturday December 23 to Tuesday, December 26, 1721

The Creditors of Mr. John Law have met at the Notary Maignan’s, to consider the properest methods ot recover their Debts.

The Evening Post, London England: From Saturday November 10 to Tuesday November 13, 1722

Hague, November 5: The Committee of Council, nominated in inspect the Affairs of Mr. John Law, have given Judgment for the Sale of his Real Estate.

John Law who had been born into a family of bankers, believed that money was only a means of exchange that did not constitute wealth in itself. He received a pardon in 1719, moved to London, then to Venice where he died a poor man on March 21, 1729.

Law thereby launched one of the first modern public relations campaigns to convince thousands of Frenchmen of the fortunes to be made in a Louisiana rich in gold and fertile land. For two years, frenzied speculation shot the value of Mississippi Company stock upwards as Frenchmen of all persuasions rushed to invest their savings. But, by 1720, when no bonanza of dividends had been forthcoming, the company collapsed when thousands of Frenchmen rushed to unload their shares, and Law fled France just ahead of an irate mob.

Both Spain and France proved unable to hold New Orleans as part of an empire against the Americans flooding into the Mississippi Valley after 1800. Napoleon tried to reestablish the French Empire in Louisiana, taking control of New Orleans from Spain in 1802; but financial troubles and the difficulty of holding French conquests in Europe and the Caribbean led him to sell all of Louisiana, including New Orleans, to the United States. In December 1903, Thomas Jefferson had pulled off one of the great real estate buys in history.

Commercial families from many European countries established branches in the city, and John Law's efforts accounted for 2,000 German immigrants. Spain made serious attempts to encourage Spanish emigration, settling several thousand Canary Islanders in the 1780's twenty miles south of New Orleans and also to the west of New Iberia. Ironically, the biggest influx under Spanish rule was that of French-speakers: the Acadians who, expelled by the British from Canada, settled from the late 1760's through the late 1700's on all sides of the city, particularly to the west, near modern Lafayette. In the last years of Spanish rule, growing numbers of Americans settled and around New Orleans.

John Law's efforts to raise funds accounted for 2,000 German immigrants. Spain made serious attempts to encourage Spanish emigration, settling several thousand Canary Islanders in the 1780's twenty miles south of New Orleans and also to the west of New Iberia. Ironically, the biggest influx under Spanish rule was that of French-speakers: the Acadians who, expelled by the British from Canada, settled from the late 1760's through the late 1700's on all sides of the city. In the last years of Spanish rule, growing numbers of Americans settled and around New Orleans.

New Orleans and American Annexation

|

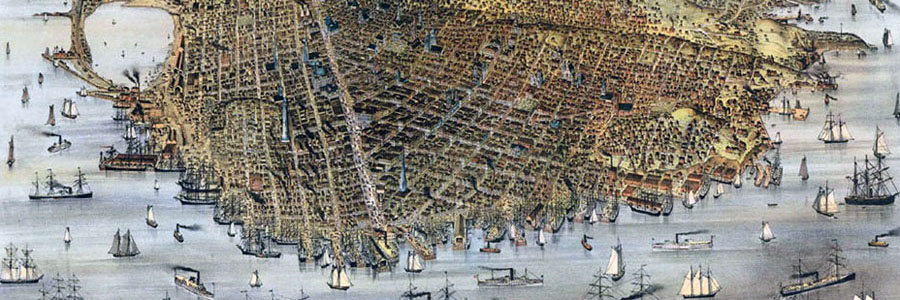

The Levee, New Orleans, 1884 Currier & Ives. |

For New Orleans, American annexation brought population growth and economic development. The Louisiana Purchase removed the political barriers to the development of New Orleans' natural economic and situational advantages. From 1803 until 1861, New Orleans' population increased from 8,000 to nearly 170,000. The 1810 census revealed a population of 10,000 making New Orleans the United States' fifth largest city, after New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore and the largest city west of the Appalachians. From 1810 until 1840, New Orleans grew at a faster rate than any other large American city.

In 1803, New Orleans was basically 8,000 people directly or indirectly tied to moving goods from river vessels to dock to ship and vice versa. Its primary industry was the port, moving and storing goods. Ship chandling, repairing, and building were a distant second industry, but rapid economic growth after 1803 spawned new economic interests.

October 10, 1818,آ London Times, London, Middlesex, United Kingdom

A New Orleans paper of the 7th inst states, that a vessel had arrived at that port with the intelligence of the Patriot and Spanish squadrons having met near the coast of Terra Fuego; that Aury, not being able to escape from the Spanish frigate, of 38 guns, on account of her superior sailing, determined to carry her by boarding, which he effect, and a few hours afterwards he died on board of his prize of wounds he had received in the contest. The frigate was sent direct from the Governor of Cuba, in pursuit of Aury's squadron. The frigate is now cruising off Carthagena, under Patriotic colours.

By the 1820's and 1830's, New Orleans was the commercial and financial intermediary for goods from all reaches of the Mississippi.

The first steamboat came down river in 1812, providing a more efficient of transportation for cotton. In 1821, 287 steamboats arrived in New Orleans; by 1826, there were 700 steamboat arrivals. In 1845, 2,500 steamboats were recorded, and during the 1850's an average of 3,000 steamboats a year called at the city.

After 1830, then, steamboats were in general use on the Mississippi, allowing two-way packet lines to operate, carrying both cargo and passengers on regular schedules.

October 30, 1857,آ California Farmer and Journal of Useful Sciences

Business of New Orleans.

The business relations of Philadelphia with New Orleans, says the Philadelphia Shipping List, have been, materially affected by the system of railroads through the central West. Merchandise which formerly came to us by way of New Orleans, now reaches us by this new course of transportation.

The annual statement of trade, published in theآ New Orleans Price Current, speaks of the comparative failure of the cane crop as the most marked feature of the year. The crop fell ten millions of dollars short of the previous year! On the other hand the cotton crop shows about fifteen millions excess. The total value of the products received from the interior was $158,071,369. This is an increase over last year of nearly $14,000,000; and in twelve years an increase of 250 per cent. The exports of produce and merchandise show an increase of nearly $9,000,000 over last year.

Of cotton the total receipts at New Orleans for the year were one and a half million of bales, the average price being 124 cents per pound. Of this. there were shipped to Great Britain 749,485 bales; to France. 258,103; to other parts of Europe, 186,069; and, to United States ports, 223,204. The entire crop of the South is estimated to have been a little short of three millions of bales.

The sugar crop of 1856 is placed at 81,373,000 pounds, against 254,569,000 the previous year. This was the product of 931 sugar houses. It is estimated that the entire crop averaged 10 cents per pound, which brings the money amount to about one-half the previous year. The average price of molasses has been about 55 cents, against 30 cents last year, and 18-1/2 cents the year previous.

The exports of tobacco from New Orleans in 1850-57 were 50,181 hhds, against 59,074 the previous year. As a tobacco market the city does not appear to be advancing.

The exports of flour for the year were 904,910 bbls. This is an increase, but the exports of western meats have diminished. The exports of whiskey were 60,058 bbls an increase over the previous year.

Currier & Ives. Champions of the Mississippi

The shipping of New Orleans does not seem to be on the increase. The interior railroad progress is against it. Flatbed boats, which were once the main river vessels, virtually disappeared after 1857.

In spite of the huge volume of steamboats that called at the city annually, New Orleans never became a center for building either ocean vessels or riverboats before the Civil War. As it grew larger, the city's location at the bottom end of the steamboat market made it a less attractive choice for steamboat construction than more centrally located cities, like St. Louis or Cincinnati.

March 19, 1873,آ Sacramento Daily Union, Sacramento, California, U.S.A.

Grain Shipments Via New Orleans

The exorbitant charges lor transportation from Chicago to New York have compelled Western farmers to look out for some other channel for shipment of their grain. In combination with the merchants of St. Louis they have tried the experiment of sending their grain down the Mississippi and shipping it from New Orleans to Europe.

The Chicago papers assert that this experiment has proven a failure that the warmth and humidity of the climate render success by the new route impossible, and that cargoes shipped from New Orleans have arrived at Liverpool "in a rotten condition." These statements are denied and apparently successfully refuted by theآ St. Louis Republican. That paper says the St. Louis Grain Association has shipped about twenty cargoes of grain from New Orleans to Liverpool, and that all but two cargoes arrived in excellent condition. The two cargoes which were slightly damaged, had suffered merely from want of care in battening down the hatches and the consequent admission of bilge water. These damaged cargoes were sold by Patterson Brothers at a higher price than Chicago wheat of the same grade which arrived on the same day by way of New York.

Theآ Republicanآ also asserts that last year fifty ships with cargoes of corn sailed from New Orleans, forty-nine of which arrived in English and French ports in excellent condition, and that the cargoes realized better prices than those of equal grade from Philadelphia, New York and Boston. The damaged cargo was not by any means in an unmarketable condition. The experience of California grain shipment seems to sustain the St. Louis theory. Our own grain crosses the equator twice before it reaches Europe, and is exposed to the heat of the tropics much longer than the wheat would be by the New Orleans route. Grain is shipped from St. Louis to New Orleans in barges and is transferred with but little delay to the ship. In five days from New Orleans the ship reaches the latitude of New York. As the northern railroads are clogged up with freight, and as the rates of transportation constitute an actual barrier to shipment, new outlets must be obtained.

To secure this object the Government is asked to aid in building the Kanawha and James River Canal, a single tunnel of which will cost $35,000,000. This canal would connect the waters of West Virginia and Virginia across the Alleghenies and Blue Ridge and would convey the grain of the Mississippi Valley to Norfolk or some new shipping port near the mouth of the James river. The shipment by way of New Orleans would probably cost less than by way of Virginia after the canal was built, but its construction, if begun, would require many years time. If the theory of safety as to climate shall prove to be correct the shipment of grain from New Orleans must increase very rapidly. As nobody can as yet exact tolls on the great Mississippi, and as its capacity for floating barges is not likely to be overtaxed, the new route will possess permanent advantages which cannot be claimed for either railroad or canal, whatever may be their capacity.

September 30, 1892,آ Sacramento Daily Union, Sacramento, California, U.S.A.

FORCED TO FIGHT

A New Orleans Crew Sue the Owners of a Steamship.

New Orleans, Sept. 29. Fifteen of the crew and one passenger of the steamshipآ Pizzatiآ will to-day file a suit for $100,000 damages in the Federal Court against the owners of the steamer. ThePizzatiآ was engaged by the Honduras Government, and, some months ago, during the revolution, was turned into an armed cruiser. She rendered valuable services in fact, succeeded in putting an end to the troubles. She shipped a crew in this city, and the crew aver that they shipped as commercial seamen, but were forced to fight. It is claimed the boat cannot be prosecuted under the Neutrality, Piracy and Shipping Acts.

July 18, 1898,آ Los Angeles Herald, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A.

The Freight Rate War

SAN FRANCISCO, July 27. The Southern Pacific, in order to meet the reductions of the Panama line and the clipper vessel, has again reduced rates for the following commodities: Wine in wood, applying from all wine shipping points in California to New Orleans, Galveston, Houston and New York, to 40 cents; glue, 40 cents; rags, 50 cents; rubber junk, 50 cents, and canned salmon, 40 cents. The rates on the last four commodities apply from all California terminals to New Orleans and New York.

Ocean-going ship building was slow to develop for similar reasons. Attempts were made in the 1850's to enlarge New Orleans' shipyards, but Northeastern financial sources were not interested in starting new shipyards to compete with the already well established Atlantic seaboard shipbuilding industry. By 1860, New Orleans did have fledgling machine shops, ironworks, several shipbuilding firms, located mainly on the westbank in Algiers. Algiers also supported a dry dock and a ship repair industry, so that in all, over 500 men were employed in ship repair and building by 1861.

However, the Civil War slowed the development of the industry, delaying for decades the emergence of a major shipbuilding industry in New Orleans.آ

As a seaport and major point of entry for the country, New Orleans always had a transient population of seamen, immigrants, and tourists, and what might be called a "hospitality" industryقrestaurants, theatres, operas, bars, gambling houses, and redlight establishments. This industry has always been much larger than what the resident population alone would support. The streets near the docksقin, above, and below the French Quarterقwere lined by bars, flophouses, and clip joints.

Visitors of all classes seemed to enjoy the luxuries, and perhaps the depravities, of the city that care forgot. Residents also enjoyed cultural and recreational opportunities far beyond what most cities of New Orleans' size could offer.

French Quarter Manual: An Architectural Guide

Malcolm Heard

Numerous black and white photos are presented along with explanatory text and captions discussing the history and describing the features of various styles, and of particular buildings. Arrangement of information is in sections on types of French Quarter houses; components of French Quarter buildings an illustrated "parts" list focusing on doors, windows, shutters, stairways, dormers, and carriageways, among others; and the many styles represented in the Quarter an illustrated "glossary" covering 16 styles, among them French colonial, Spanish colonial, federal, Greek revival, Gothic revival, Italianate, Egyptian revival, Craftsman, 20th-century restoration, and modernism. Spiral wire binding (in a hard cover). Annotation c. by Book News, Inc., Portland, Or.

The French Quarter:آ

An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworldآ

Herbert Asbury

Home to the notorious "Blue Book," which listed the names and addresses of every prostitute living in the city, New Orleans's infamous red-light district gained a reputation as one of the most raucous in the world. But the New Orleans underworld consisted of much more than the local bordellos. It was also well known as the early gambling capital of the United States, and sported one of the most violent records of street crime in the country. In The French Quarter, Herbert Asbury, author of The Gangs of New York, chronicles this rather immense underbelly of "The Big Easy." From the murderous exploits of Mary Jane "Bricktop" Jackson and Bridget Fury, two prostitutes who became famous after murdering a number of their associates, to the faux-revolutionary "filibusters" who, backed by hundreds of thousands of dollars of public support though without official governmental approval undertook military missions to take over the bordering Spanish regions in Texas, the French Quarter had it all. Asbury takes the reader on an intriguing, photograph-filled journey through a unique version of the American underworld.

New Orleans Irish:آ

Arrivals, Departures

John Finn

Begins with Ireland of Ancient Times and continues on to 1845 - 1847, during the famine and then on to Louisiana. It gives the Famine Ship Lists from 7/22/1847 to 6/29/1848. Then goes on to list cemetery listings in St. Patrick's 1, 2 and 3, military, etc. There are quite a few pictures, some diagrams of the cemeteries and some family stories.

River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom

Walter Johnson

Through mining journals, correspondence, public records and popular literature, Johnson reminds us that New Orleans, not Richmond, was the engine of Southern prosperity: its largest city, largest slave market and the center of a booming international trading system. Mixed with fascinating anecdotes, grim accounts of slave life and a convincing argument for plantation slavery of any people was "essential" to the role in the 19th century's burgeoning industrial capitalism. While this book refers to America's slavery, as soon as national started sailing around the globe, they enslaved villages and countries around the world to do their bidding and increase their countries coffers: China, India, Ireland, Africa, the Caribbean.

The Militant South, 1800-1861

آ

John Hope Franklin

The author identifies the factors of the South's festering propensity for aggression that contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. Franklin asserts that the South was dominated by militant white men who resorted to violence in the face of social, personal, or political conflict. Fueled by their defense of slavery and a persistent desire to keep the North out of their affairs, Southerners adopted a vicious bellicosity that intensified as war drew nearer. Drawing from Southern newspapers, government archives, memoirs, letters, and firsthand accounts, Franklin masterfully details the sources and consequences of antebellum aggression in the South. First published in 1956, this classic volume is an enduring and impeccably researched contribution to Southern history. This paperback edition features a new preface in which the author discusses controversial responses to the book.

Patriot Pirates: The Privateer War for Freedom and Fortune in the American Revolution

Robert H. Patton, grandson of the battlefield genius of World War II, writes that during America s Revolutionary War, what began in 1775 as a New England fadق converting civilian vessels to fast-sailing warships, and defying the Royal Navy s overwhelming firepower to snatch its merchant shippingق became a massive seaborne insurgency that ravaged the British economy and helped to win America s independence. More than two thousand privately owned warships were commissioned by Congress to prey on enemy transports, seize them, and sell the cargoes for prize money to be divided among the privateer s officers, crewmen, and owners.

The Jews of the United States:

1654-2000

Hasia R. Diner

Since Peter Stuyvesant greeted with enmity the first group of Jews to arrive on the docks of New Amsterdam in 1654, Jews have entwined their fate and fortunes with that of the United States ق a decision marked by great struggle and great promise. What this interconnected destiny has meant for American Jews and how it has defined their experience among the world's Jews is fully in this work, a comprehensive and finely nuanced history of Jews in the United States from 1654 through 2000.

The Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf

William C. Davis

During a most colorful period in New Orleans' history, from just after the Louisiana Purchase through the War of 1812, privateers Jean and Pierre Laffite attacked Spanish merchants on the Gulf. They were pirates to the U.S. Navy officers who chased them and heroes to the private citizens who shopped for contraband at their well-publicized auctions. They were part of a filibustering syndicate that included lawyers, bankers, merchants, and corrupt U.S. officials. Allegiances did not stop the Laffites from becoming paid Spanish spies, disappearing into the fog of history after selling out their own associates.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.