Nova Scotia

° British Columbia (Vancouver and Vancouver Island)

° Edmonton ° Halifax

° Hudson Bay

° Manitoba

° Montreal

° Newfoundland and Labrador (St. John's)

° Ontario

° Ottowa

° Quebec

° Regina ° Toronto ° Winnipeg

° The Maritime Provinces: New Brunswick and Nova Scotia

International Harbors

Halifax, Nova Scotia was founded by British General Edward Cornwallis in 1749. The British created Halifax to act as a naval and army base to protect them from the French who had established the town of Louisbourg on the northern island of Nova Scotia. Halifax acted as a British naval base until 1906 when the Canadian government took it over.

Before Cornwallis arrived at this southern, peninsular area of Nova Scotia with 2,500 British settlers, the area had acted as a French fishing station. Beginning in the 17th century, the French and the British had struggled over control of the Atlantic provinces of Canada, most specifically Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The French-speaking people living in the areas of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, known as Acadians, were unique people; French, Scottish, Irish and even Portuguese influences were apparent in their culture. About 8,000 Acadians lived in these areas when the British claimed them as their own in the mid-18th century.

The Acadian Diaspora: An 18th-Century History

Late in 1755, an army of British regulars and Massachusetts volunteers completed one of the cruelest, most successful military campaigns in North American history, capturing and deporting seven thousand French-speaking Catholic Acadians from the province of Nova Scotia and News Brunswick, and chasing an equal number into the wilderness of eastern Canada.

Thousands of Acadians endured three decades of forced migrations and failed settlements that shuttled them to the coasts of South America, the plantations of the Caribbean, the frigid islands of the South Atlantic, the swamps of Louisiana, and the countryside of central France. The Acadian Diaspora tells their extraordinary story in full for the first time, illuminating a long-forgotten world of imperial desperation, experimental colonies, and naked brutality.

Using documents culled from archives in France, Great Britain, Canada, and the United States, in The Acadian Diaspora,

Christopher Hodson reconstructs the lives of Acadian exiles as they traversed oceans and continents, pushed along by empires eager to populate new frontiers with inexpensive, pliable white farmers. Hodson's narrative situates the Acadian diaspora within the dramatic geopolitical changes triggered by the Seven Years' War. Faced with redrawn boundaries and staggering national debts, imperial architects across Europe used the Acadians to realize radical plans: tropical settlements without slaves, expeditions to the unknown southern continent, and, perhaps strangest of all, agricultural colonies within old regime France itself. In response, Acadians embraced their status as human commodities, using intimidation and even violence to tailor their communities to the superheated Atlantic market for cheap, mobile labor.

By 1800 many Acadians had returned.

The Maritime Provinces, or Maritimes, Canada, refers to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, which before the formation of the Canadian confederation (1867) were politically distinct from Canada proper.

This clash of cultures lasted through the 19th century and many Acadian influences can still be seen in the area.

During the early 19th century, 2,000 black loyalists who had fought for the British in the War of 1812 moved to Halifax, establishing the beginnings of a black community in Halifax.

The 1830s brought the first group of Irish Catholics into Halifax, introducing a new religion to the city which had previously been Protestant.

Nova Scotia. Newfoundland. |

By 1851 Halifax's population had grown to 20,749. The first half of 19th century was quite a prosperous time for Halifax. Halifax's harbor was busy; trade between New England and Canada was friendly and profitable.

In 1854, Canada and the United States, signed the Reciprocity Treaty which allowed duty free trade between the two countries. However, the treaty was not renewed in 1866 because the United States was suspicious that Canada had supported the Confederate army along with the British.

By the second half of the 19th century Halifax's trade started slowing down. Canadian tariffs further discouraged ships from docking in Halifax and soon the US ports became more desirable. However, Halifax continued to develop as a city. In 1866 the first street railway system was put into place and by 1896 Halifax had an electric streetcar system. In 1890 Halifax opened its first city hall and in 1906, the Canadian government officially took over the army and naval base in Halifax from the British.

October 21, 1866, Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, London, United Kingdom

BEWARE OF CONFEDERATION

We return to the subject of the confederation of our North American provinces; because the banquet which was recently given to the distinguished delegates from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, appears to have hastened the public mind at a dangerous speed to a conclusion on this vitally important subject. At the banquet there were no opponents of confederation. It seemed as though nothing remained to be said against the fusion of our vigorous American colonies into a vast political whole.

Nobody had less to say, that was worth studying, than Lord Carnarvon. He tried to be oratorical, and failed; and he promised the delegates the respectful attention of her Majesty's government but he showed no knowledge whatever of the condition of public opinion in the Canadas, or the maritime provinces. It is impossible to gather From Lord Carnarvon's speech even a hint at the direction to which the government leans: but they will incline, we suspect, to the popular side. It is of importance that the popular side should be the right side: we make no apology, therefore, for returning to the weighty paper against Confederation, which has been issued by the Hon. Joseph Howe. We have already indicated the main points or some of the main points of Mr. Howe's argument; but we shall now take the liberty of adding some of his facts and of quoting one or two vigorous passages in which he supports them.

The reader is startled at the outset by finding the confederation of our American colonies denounced as "a measure of spoliation and appropriation, on a more gigantic scale than any that has startled Europe." According to Mr. Howe, the idea of confederation has "convulsed society in British America" for two years. He is astonished to find that it has defenders in England: the fact being that it has hardly any opponents.

Mr. Howe is very severe on Canada. He describes her as sparsely populated, as "overlapped" by the great republic, as "at the mercy of the chapter of accidents," as " frozen up for five months of the year," and as deficient in political wisdom. He points to the Canadians' violent and never-ending feuds ; and to the burning of the parliament house at Montreal; and then he asks whether such politicians are to be made the almost absolute rulers over the maritime provinces of British America, which are not chargeable with such excesses? Mr. Howe puts this case in behalf of the maritime provinces:

"For a hundred years some of them have worked representative institutions in peaceful subordination and devoted loyalty to the crown and parliament of England; and, for a quarter of a century, since responsible government was wisely conceded to them by the mother country, they have developed that system with skill and ability worthy of all praise. Had those provinces been under the control of Canada in 1837, or had they been imbued with the spirit of disaffection, they would have cut off the troops marching through them in mid-winter; and, in a month, fifty thousand sympathisers would have crossed the American frontier, and British America, in all human probability, would have been wrested from the crown. Had they sympathised with those who, with the settled purpose of throwing off their allegiance in 1849, got up the emeute at Montreal, the complications would have been serious, and the ultimate results extremely doubtful."

It is notorious that the maritime provinces stood firm to their allegiance; that they rebuked the Canadians; and that they have never felt any respect for their political abilities. They have been spectators of the long quarrel between the upper and lower provinces of Canada; and are not anxious to be governed by the chief actors in it . . .

". . . From all these complications and difficulties the maritime provinces are now free; and surely they may be paidoned if they have no desire to be mixed up with them. Their system is very simple. They govern themselves as completely as any other British provinces, or any states of the American union, in perfect subordination to the government and parliament of the empire. They owe no allegiance to Canada, are free from her antagonism of races from her sectional rivalries from her dual leaderships and double majorities from her ever recurring political crises and deadlocks; and being free from them, they naturally desire to preserve the great privileges they enjoy, and to develop their resources, without being involved in entanglements difficulit to unravel, and from which, when once entralled, there may be so easy means of escape.

Surely this view of confederation is worthy the closest attention. Let us have a care lest we alienate the affections of the colonists of the maritime provinces. Of their loyalty there has never been the least question; while Canada has threatened disloyalty more than once. The passion which has entered into the controversy that is now raging between Canada and the maritime provinces; may be imagined from the daring with which Mr. Howe describes the public men of Canada as more ambitious than Bismarck and the Emperor Napoleon. He dwells on the importance of our independent maritime provinces, as nurseries for our navy . . .

|

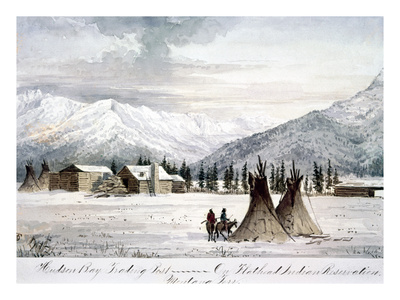

| Trading Outpost, c. 1860 |

| Peter Petersen Tofft |

1899. World's Fleet. Boston Daily Globe

Lloyds Register of Shipping gives the entire fleet of the world as 28,180 steamers and sailing vessels, with a total tonnage of 27,673,628, of which 39 perent are British.

| Great Britain | 10,990 vessels, total tonnage of 10,792,714 |

| United States | 3,010 vessels, total tonnage of 2,405,887 |

| Norway | 2,528 vessels, tonnage of 1,604,230 |

| Germany | 1,676 vessels, with a tonnage of 2,453,334, in which are included her particularly large ships. |

| Sweden | 1,408 vessels with a tonnage of 643, 527 |

| Italy | 1,150 vessels |

| France | 1,182 vessels |

For Historical Comparison

Top 10 Maritime Nations Ranked by Value (2017)

| Country | # of Vessels | Gross Tonnage (m) |

Total Value (USDbn) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Greece | 4,453 | 206.47 | $88.0 |

| 2 | Japan | 4,317 | 150.26 | $79.8 |

| 3 | China | 4,938 | 159.71 | $71.7 |

| 4 | USA | 2,399 | 55.92 | $46.5 |

| 5 | Singapore | 2,662 | 64.03 | $41.7 |

| 6 | Norway | 1,668 | 39.68 | $41.1 |

| 7 | Germany | 2,923 | 81.17 | $30.3 |

| 8 | UK | 883 | 28.78 | $24.3 |

| 9 | Denmark | 1,040 | 36.17 | $23.4 |

| 10 | South Korea | 1,484 | 49.88 | $20.1 |

| Total | 26,767 | 87.21 | $466.9 | |

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.