San Francisco News and Stories

Due in part to continuing superstitions about women at sea, few women lived on board permanently prior to the 1700s. And of those who did travel the high seas, only a few were wives. Her Majesty's Navy under Admiral Nelson traveled with unmarried women for the convenience of her officers, even though it was against the law. In 1822 an anonymous pamphlet suggested that members of the Royal Navy were taking as many as two women apiece aboard the ships. These women also proved useful in that they fought alongside their lovers at the Nile and Trafalgar.

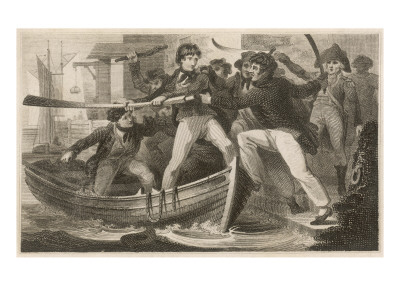

By the early eighteenth century, adventurous women like Mary Anne Talbot, Anne Bonny, and Mary Read had begun to join ships' crews disguised as men.

|

Mary Anne Talbot took to the sea disguised as "John Taylor," to follow a young naval officer who did not return her passion. She was sufficiently graceless to pass for years unquestioned. She was discovered only when a broken knee forced her into the hospital.

Anne Bonny was the Irish daughter of a lawyer who sailed to the West Indies and married the pirate John Rackham (also known as Calico Jack).

During the Napoleonic Wars, wives began accompanying their husbands aboard warships. Since there was no shore leave, a few captains allowed wives to share their husbands' hammocks and rations, and in many cases these women performed important duties in battle.

As the century wore on, merchant and whaling captains began to take their wives to sea for long voyages, convinced that the value of their mutual companionship outweighed the dangers of life at sea. Mary Russell, a whaling wife who kept a journal, wrote that when ships were close enough for visits on the high seas, social activities included parties, concerts, croquet, picnics and Bible study. By the early 19th Century, vessels with women aboard were referred to as Hen Frigates.

A New Zealand-based maritime historian, Joan Druett, wrote of these ships and the women aboard in her book of the same name: Hen Frigates: Passion and Peril, Nineteenth-Century Women at Sea

(May, 1999).

Some captain's wives, such as Eleanor Cressey and Mary Patten proved to be valuable navigators and earned the respect of even the hardest old salts. Many sailed with their husbands on merchant vessels and whalers because otherwise they might not see their mate for as much as six months or a year.

The ladies met up with each other in harbors around the world. When they found friends in foreign ports, the women gathered for meals which included considerable amount of sherry, champagne and schnapps along with picnic fare and chowder. Sherry and gin were popular in East Indian ports, while dark beer, whiskey punch and wine were featured in London.

Wives were expected to charm passengers and visiting captains who were met during voyages.

When steamships began operating in the 1850s on regular and quite short schedules -- as compared to sailing vessels, which could be caught in doldrums for days or weeks on end -- many women began staying home. One wife that sailed with her husband, and even had a baby on board off the coast of Mexico, was Henrietta Emelia Osborne Blethen, wife of Captain James H. Blethen. She had the misfortune of being on board with their child, who previously had not set foot on land, on the night that Captain Blethen's ship, the North America wrecked off the Coast of Mexico. All passengers and hands were saved, the ship and much cargo lost, and Captain Blethen, with wife and child (in a champagne basket at his side), walked across Mexico to catch a steamer back to New York. Children born aboard ship were considered good luck to the vessel, however, it proved not so in this case.

In July of 1876, Annie Brassey, wife of Tom, commander of the 531-ton schooner Sunbeam, left England for a circumnavigation of the globe. Also on board were a nanny for the Brassey's four children, a stewardess, four stewards and three cooks, plus a doctor, four guests, two dogs, three birds and a kitten. After 37,000 miles at sea, which included a fire aboard the Sunbeam in the Sea of Japan (extinguished by Mrs. Brassey), and pleasant visits to points around the world, including the South Seas, they returned home on May 26, 1877. Lady Brassey wrote:

I travell'd among unknown men,

In lands beyond the sea,

Nor, England did I know till then

What love I bore to thee

The Discovery of Jeanne Baret

A Story of Science, the High Seas, and the First Woman to Circumnavigate the Globe

Glynis RidleyIn 1765, eminent botanist Philibert Commerson had been appointed to a grand new expedition: the first French circumnavigation of the world. As the ships’ official naturalist, Commerson would seek out resources—medicines, spices, timber, food—that could give the French an edge in the ever-accelerating race for empire.

Jeanne Baret, Commerson’s young mistress and collaborator disguised herself as a teenage boy and signed on as his assistant. The journey made the twenty-six-year-old, known to her shipmates as “Jean” rather than “Jeanne,” the first woman to ever sail around the globe.

When the ships made landfall, Baret carried heavy wooden field presses and bulky optical instruments over beaches and hills. She had spent months perfecting her masculine disguise in the streets and marketplaces of Paris. Expedition commander Louis-Antoine de Bougainville recorded in his journal that curious Tahitian natives exposed Baret as a woman, eighteen months into the voyage. But the true story, it turns out, is more complicated.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.

Copyright ~ 1998-2018.